Episode 42: Vengeance in the Solomons

Following the allied campaigns in the lower Solomons and eastern New Guinea MacArthur and Nimitz were prepared to continue their drives into Japanese territory. The two services represented by MacArthur and Nimitz had two different ideas about how to get to the Japanese home islands. MacArthur wanted to advance along the Solomons and the northern coast of New guinea to prepare for an invasion of the Philippines and thence to Japan. Nimitz would take the Navy and Marine Corps through the central pacific along the Marshall, Caroline, and Marianas islands after which he would strike at Nippon itself. In both cases the American planners were faced with the prospect of invading and seizing countless islands, or at least that's what the Japanese had assumed.

For the Japanese each tiny spit of land had intrinsic value as something to be conquered. For the Allies their value was incidental or worth as much as it offered in getting them that much closer to defeating Japan. If a particular island or stronghold provided no strategic benefit from its seizure then it would simply be left to “whither on the vine” as they said. Thus the island hopping strategy was born.

In early 1943 only the earliest of footholds had been established but the Japanese were decidedly on the backfoot after losing Guadalcanal. MacArthur’s proximate objective was Rabaul on the island of New Britain, the seat of the Japanese Eighth Army. The plan to seize Rabual was codenamed Operation Cartwheel and involved a dual envelopment of the stronghold from north and South. MacArthur would take the southern route continuing along New Guinea, and Admiral Halsey, commander of the South Pacific Area, would take the northern route along the remainder of the Solomon chain.

Meanwhile the Japanese were planning their defense of the islands. In overall command of the regional defense was General Hiroshi Immamura with the 17th and 18th Armies at his disposal. The 17th Army area of repsonisbility encompased the remainder of the Solomon chain and the 18th would defend Northern New Guinea. The 18th Army was newly assigned to the region and thus was not yet in position in early 1943 and thus had to be convoyed in. General MacArthur’s air commander, General George Kenney, sought to take advantage of that. The result was the battle of the Bismarck Sea.

General Kenney had arrived in the theater only in August 1942 but he was a leader in updating the Army Air Force’s anti-ship tactics. He helped to end the practice of high altitude bombing against surface vessels and began training his aircrews on low altitude attacks utilizing machineguns, skip bombing, and mast-height bombing. Skip bombing was exactly waht it sounds like. Several hundred yards from their their target aircraft would release bombs which would skip along the waters suface like a stone similar to the methods used by the RAF against german dams in europe. MAst-height bombing was similiar except that the bombadier would release his bomb right at the exact moment that would cause the explosive to hit its target directly on the side of the hull. Key to these bombing technieuqes was nuetralizing the defender’s anti-air capability which is where strafing runs came in. Fighters would come in fast and low to strafe the ships with the intent of destroying their AA guns. Kenney’s men would get to test out their new techniques against the ships carrying the 51st Division of the 18th Army from Rabaul to Lae in New Guinea.

On February 28th, 1943 the Japanese convoy departed Rabaul under the cover of tropical storms that were sweeping through the island chain. It consisted of eight transports and eight destroyers carrying 6900 men between them and escorted by 100 fighters Their luck only held out for about two days before the storm clouds cleared and the skies became suitable for air operations on March 1st. General Kenney had 200 bombers and 150 fighters in New Guinea at his disposal along an additional 85 bombers and 95 fighters in Australia so when the opportunity presented itself he was ready to seize on it. As the clouds parted around 3:00 in the afternoon the convoy was spotted by a patrolling B-24 liberator.

Kenney, seeing his chance, leapt at it. The next morning, while waiting for scouts to regain contact with the convoy, he dispatched a flight of Australian A-20 to attack Lae in New Guinea in order to prevent them from sortieing to defend the convoy. When contact with the convoy was reestablished by another patrolling liberator at about 10 Am on March 2nd Kenny sent his first sortie against the convoy. The attacking force was composed of eight B-17s in the first wave and another 20 in the second. They soon found their targets where they engaged with Japanese fighters and dropped their payloads at the Japanese ships.

The initial attack was a partial success. One transport ship was sunk with 1200 Soldiers aboard and two others were damaged along with eight Japanese fighters knocked from the skies. In exchange nine B-17s were damaged but returned to their bases. Not a bad result for the initial run but General Kenney was nowhere near done with the Japanese. By the close of March 3rd he would throw 350 aircraft at the convoy sinking all the transports and half the destroyers. The effort was devastating to the Japanese plans to reinforce New Guinea from the Solomons. Only a fraction of the troops bound for Lae actually arrived, about 1,200 or so.About 2,700 men were fished from the waters of the pacific to return to Rabaul and 2,800 were lost at sea. Of all the aircraft launched by the allies in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, as it came to be known, only two bombers and four fighters were shot down for a total loss of only 13 lives. An incredible exchange ratio that I think any commander would take.

The catastrophic failure to reinforce New Guinea resulted in the Japanese significantly altering their procedures for sustaining the island. No longer would they dispatch convoys without air cover and they would gradually transition to resupplying and reinforcing at night while hiding in the many coves and inlets during the day. This traffic was eventually intercepted and reduced a trickle by indigenous coastwatchers who reported Japanese movements to allied command.

Meanwhile Admiral Yamamoto was planning retribution for the loss of Gudalcanal. Under the auspices of Operation I-Go he assembled a force a 350 aircraft, a veritable armada in 1943 terms, to sink American shipping supplying Guadalcanal and attrit her air forces. On April 7th he saw his opportunity. A force of 25 vessels including four cruisers was steaming down Iron Bottom Bay and Yamamoto believed it to be the ideal target.

Coastwatchers in New Georgia detected the strike force. Unable to count the vat number of aircraft flying overhead they simply reported “hundreds” of aircraft in-bound. Tulagi and Guadalcanal scrambled what fighters they could but the combined force of Army, Navy, and Marine Corps aircraft totaled only 67. The allied airmen put up stiff resistance however, one rookie pikot, Marine lieuteant Jimmy Swett, shot down seven Japanese bombers becoming an Ace in one mission. For his exemplary performance he was awarded the Medal of Honor but he was far from the only pilot to go above and beyond that day. All over the lower solomons pilots and AA gunners were adding to their kill counts. In all 39 Japanese aircraft were shot down for a loss of seven allied aircraft with all pilots recovered.

The Japanese only managed to sink one destroyer, one tanker, one corvette, and two dutch transports but they reported much greater success. Japanese aircrew exaggerated their success to their superiors who in turn embellished on those reports until they reached Yamamoto who was told there had been a massive victory in the Solomons. Believing his men had achieved an overwhelming victory he canceled follow-on strikes and planned a visit to Bougainville in order to encourage his men after their recent successes. News of the Admiral’s imminent arrival was transmitted to Rabaul and, considering American signalmen had long ago cracked Japanese Naval codes, this proved to be a disastrous decision.

When Nimitz was made aware of Yamamoto’s travel to New Britain by air, he decided they should try to get him, initiating Operation Vengeance. The Air commander for the Solomons area gave the assignment to the 339th Fighter Squadron equipped with P-38 lightnings, the longest range fighters available. On the Morning of April 18th Yamamoto was scheduled to fly from Rabaul to Kahili airfield on Bougainville. His air escort consisted of two Betty Bombers and nine zeros. With him were his chief of staff and several other key staff members. That same morning 16 P-38’s rose form Henderson field on Guadalcanal to intercept the admiral. Just as the Bettys were descending into the airfield the P-38s ambush them from higher altitude sending the two bombers down almost immediately, one went crashing into the jungle and the other careening into the bay. Three of the zeros went down with them.

The mission was a resounding success, the architect of Pearl Harbor and the finest mind in the Japanese military was dead. But the Americans stayed mum, they could not risk revealing that they had cracked the Japanese code. On May 21st the Japanese publicly announced that Yamamoto was dead.

The first half of 1943 was a relatively quiet period in the southwest pacific, at least as far as land operations go. After the end of the battle for Guadalcanal MacArthur and Halsey began setting the conditions for their continued advance on Rabaul. Additionally, operations in North Africa were soaking up the Navy’s ability to conduct Amphibious landings and sustain overseas forces. The only large maneuver was the seizure of the Russel islands between Guadalcanal and the New Georgia islands; however , these landings were unopposed because the Japanese had abandoned the Russels shortly after the fall of Guadalcanl. By May however resources were beginning to flow back to the Pacific along with new equipment and weapons.

The Pacific campaign can be conceptually divided into three phases. The first phase was characterized by the strategic defensive in the aftermath of pearl harbor. The second phase was the effort to seize the initiative in Guadalcanal. Finally the third phase, strategic offensive, in which the allies drove the Japanese back to the home islands. The Solomons campaign beyond Guadalcanal represented the first actions in the third phase thus men and equipment were beginning to flow into the Southwest Pacific to carry that offensive forward.

New landing craft were arriving in the theater. No longer would the Marines be forced to leap from the sides of the old LCPL, or Landing Craft Personnel Light. Higgins boats, officially known as LCVPs, or Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel had finally arrived in the pacific after seeing extensive use in the mediterranean. Newer versions of the amphibious tracked landing vehicle, or simply the amtrac, were arriving as well. Though very useful for navigating up small waterways and crossing streams the older versions were susceptible to corrosion. The new alligators, as they were affectionately known on Guadalcanal, were salt resistant and featured a rear facing ramp.

The new M-1 Garand semi-automatic rifle had also begun to arrive to replace the Springfield rifles. Though warily accepted at first by the old salts for being less accurate and less durable the rifle quickly won over its detractors. Its relatively rapid firing capability soon proved its usefulness. Bazookas were also arriving to help supplement the infantryman’s toolbag. Named for a comical musical instrument used by comedian Bob Burns, it gave individual riflemen at least a basic anti-armor capability. Finally, flamethrowers were also beginning to be employed. They would prove quite useful in rooting out japanese defenders from even the most stubborn positions.

Rations too were changed in the early part of the war. The old C rations consisting of meat mixed with beans or vegetables sealed in a can were replaced with the ten-in-one ration. These proved quite popular, they could contain various meats, spam, bacon, cheese, cigarettes and coffee or tea. Though they provided more variety and included some sought after commodities they weren’t as calorie dense.

New aircraft were being fielded for the air forces as well. As mentioned already the new P-38 Lightning heavy fighter had begun operating in the Pacific woth the Army Air Corps. The Lightning was a unique aircraft if anything. Its distinctive twin engine design inspired its German nickname, der gableschwanz tuefl, or the fork-tailed devil. Personally I always thought it was a bit of an ugly baby but performance wise it was formidable. Propelled by twin supercharged engines it could propel it to 400 miles per hour and it could climb 3300 feet a minute and boasted a 1150 mile range. For armament it carried quad .50 caliber machine guns alongside a 20 mm cannon making it capable of taking down even the toughest targets including enemy bombers, tanks, and warships. Over 10,000 P-38s would be produced during the war and, perhaps surprisingly, they would score more kills against Japanese aircraft than any other fighter in the allied arsenal.

For the Navy and Marine Corps the corsair was the new aircraft to begin showing up on flight decks and airfields. The F4U Corsair, known for its distinctive reverse gull wing design was intended to be a carrier based aircraft but due to some ungainly characteristics naval aviators never took to the aircraft. Marine aviators loved it however. IT had a relatively high top speed of 400 miles per hour and had a reputation for ruggedness allowing it to survive in the relatively difficult conditions it faced in the southwest pacific. The Corsair would rack up over 2000 kills throughout the war and serve as the workhorse for some of the most famous squadrons to survive in the Pacific including Major Pappy Boyington’s Black Sheep Squadron.

Boyington, nicknamed Pappy because, at 31, he was already an old man by the reckoning of his men, was already a veteran by the start of the war. Before America entered the war he left the marines to go serve with the Flying Tigers in china where he shot down at least two but as many as six japanese aircraft. After Pearl Harbor he returned to the United States and attempted to get his commission reinstated. The Marines, believing he had left the service in a time of crisis, denied his petition so he went to work as a valet in Seattle. He didn’t give up though and continued to pester the Department of Navy until they let him back in.

Having been allowed back in the marines he was given the rank of Major despite leaving as a First Lieutenant only a year earlier. His first assignment after returning was to Guadalcanal as the XO for the 122nd Attack squadron. It wasn’t long before he received his own command however. First he was given the 112th Attack Squadron from July to August 1943 and subsequently his most famous command the 214 Marine Fighter Squadron, otherwise known as the Black Sheep. Without Boyington there would have been no Black Sheep squadron. They were a mish mash of pilots thrown into the Solomons individually so when Boyington effectively organized them the Marine Corps more or less let him have them and legitimized the organization.

After turning his band of misfits and stragglers into bona fide fighter squadron Boyington had just about three weeks at Espiritu Santo to train with them and turn them into a real fighting outfit.On September 16th Boyington got hist first opportunity to show whether he deserved his command when the squadron was assigned to escort a bomber formation oer bougainville. While on mission they were ambushed by as many as 40 Zeros and successfully fought them off Boyington shooting down five of them himself. He was already an ace on his first mission. Boyington and the Black Sheep would wreak havoc across the Solomons for five months and score 22 kills before he was shot down over rabaul and captured. For his incredible performance Boyington was awarded the Medal of Honor.

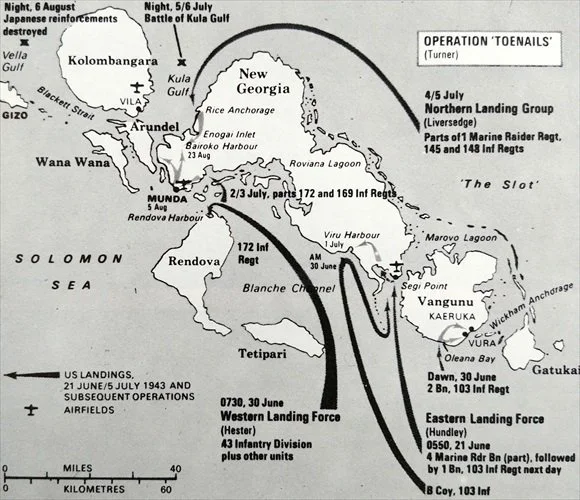

Having set the conditions to continue their drive on Rabaul in the first half of 1943 McArthur and Halsey were ready to resume the campaign. The campaign would last months and was characterized by flurries of amphibious landings, independent maneuvers and small naval battles throughout the solomon's chain and coast of New Guinea. On the morning of June 30th the campaign began in earnest when 6,000 Soldiers and Marines of Halsey’s Amphibious Force III landed to seize the New Georgia Islands consisting of New Georgia itself, Rendova, and Vangunu. The primary objective of the operation was to capture the airfield at munda point on the western tip of New Georgia to be taken by the 43rd Infantry Division. A smaller force of two Army and one Marine raider battalion, under Marine Colonel Harry Liversedge, landed on the northern coast at Rice Anchorage to block Japanese reinforcements arriving from Kolombangra about ten miles away on the other side of the Kula gulf.

The Japanese did not simply yield the seaways to the American Navy however and engaged American vessels when they felt they had the advantage. As was the case throughout the early part of the war the American radar advantage was neutralized by Japanese long lance torpedoes. American radar was often able to detect the japanese early conferring an advantage especially at night allowing them to deliver painful and accurate main battery fire however spreads of japanese torpedoes often found the bottoms of american hulls making naval engagements deadly and chaotic.

After landing Liversedges marines proceeded to establish their blocking position but were thwarted by the dense jungle and rugged terrain. Despite the marines occupying the primary trail from Rice Anchorage the Japanese were able to bypass them through small jungle trails and landing south of their position at Bairoko Harbor. This would complicate an already precarious situation in the south where the 43rd ID was encountering difficulty in their advance from Zanana toward Munda.

A combination of stiff Japanese resistance and their own inexperience contributed to the 43rds lumbering progress. Though they had been in the south pacific since October of 1942 they had yet to see any combat at all so when one of their battalions ran into a Japanese platoon defending the road to Munda it was held up for two days. The 169th Infantry Regiment would act as the spearhead driving directly for Munda but it was quickly stymied. In an effort to break through the Japanese outer defenses General Hester, commander of the 43rd ID, sent the 172 Infantry on a more northern route but this force too was blocked by the Japanese. By July 8th the advance had effectively been halted.

The Japanese usual methods of terrifying their opponents by screaming in the night and conducting infiltrations worked the 43rd over mercilessly. The men of the 43rd would fire wildly into the darkness and toss grenades at phantoms, injuring and killing their fellow Soldiers as often as the Japanese. General Sasaki, commander of Japanese troops in New Georgia, also initiated a counterattack which nearly overran the 43rds division command post. Soon, despite only participating in light engagements men began streaming to the rear with symptoms of battle fatigue. The division's poor performance did not inspire confidence in the Division’s Corps Commander Lieutenant General Oscar Griswold who informed Halsey that the 43rd ID was on the verge of collapse.

Halsey took the news seriously and relieved Hester of overall command of the operation leaving him only the 43rd ID to worry about. In his place General Griswold commanded all forces in New Georgia on July 15th, 1943.Griswold made the determination that more forces would need to be committed to the battle so sent elements of the 37th and 25th Infantry divisions. Having repulsed Saski’s counterattack the Japanese seemed to have lost much of their tenacity and with the addition of more men the tempo increased markedly. Liberal application of air and artillery support as well as 81 mm mortars and marine flame tanks also helped beat back the japanese. By August 5th Munda field was in allied hands.

Despite losing the island, General Saski had managed to withdraw most of his troops to Kolombangara rather than lose them in a doomed defense. Instead, he hoped to retake it along with its Airfield. On the night of August 6th he dispatched four destroyers laden with 900 troops into the Vella Gulf. The Japanese flotilla was soon picked up on Radar by an American force of Six destroyers under Commander Frederick Moosbrugger. Having 20,000 yards to maneuver with at night moosbrugger was able to close the distance with the Japanese undetected and unleashed a spread of torpedoes at 6300 yards. The Torpedos struck home. The Kawakaze exploded and was destroyed almost instantly. THe Hawakazi and Arashi were both severely damaged and disabled to be finished off by the 5 inch guns of the American destroyers. Only one Japanese vessel, the Shigure escaped but it had not beenferrying any troops. With hsi hopes of retaking New Georgia dashed, the island was completely secure by August 25th and the operation was concluded.

With New Georgia firmly in allied hands Kolombangara and Vella Lavella were the next two obvious objectives up the chain. General Sasaki still had tens of thousands of troops on Kolombangara and the island offered very little in the way of operational advantage so General Griswold elected to simply bypass it. The seizure of Vella Lavella was composed mostly of the 35th Infantry Combat Team of the 25th Infantry Division. The invasion was a complete success and the island was seized for minimal losses mostly because Sasaki had chosen to withdraw the balance of his forces form the island, much of which were lost in naval action that sent much of the withdrawing force to the bottom.

The New Georgia Operation exceeded its expectations. The Airfield at Munda proved to be even more useful than anticipated due to the layout of the terrain and the quality of the coral on which it was built. After its capture the allies were able to put it back into action against the Japanese almost immediately and even expanded it to be able to host aircraft of all types. Additionally, the 8th New Zealand Brigade was able to Seize the Treasury islands for minimal casualties thereby claiming the allies furthest point along the solomon's chain. The result was that not only were the Japanese eliminated from the entire New Georgia archipelago but also that four new airfields were added by mid September within 500 miles of Rabaul and only about 200 miles from Bougainville.

Of course New Georgia was not the ultimate objective of Operation Cartwheel but only a stepping stone to the ultimate goal of isolating Rabaul so allied commanders began to set their sights on the next intermediate objective: Bougainville. Allied planners decided to divide the island in half operationally and to focus on reducing and securing the southern half by the end of 1943. The Southwest Pacific group considered bypassing Bougainville entirely but ultimately concluded that the airfields in the Shortland, Ballale, and buin-Faisi areas were far too critical to allow the Japanese continued use of them.

Meanwhile MacArthur was continuing his own drive north west toward Rabaul along the coast of New Guinea. Having secured Bun and Gona his next step was to capture Lae and Salamaua about 165 miles further up the coast. To accomplish this he initiated a pincer movement against Lae. American forces would land along the coast to pressure Salamaua forcing the japanese defenders to flex support to the garrison thereby weakening the defense of Lae itself. Concurrently, Australian forces advanced along the interior route.

MacArthur’s ALAMO force had little experience and fewer resources to conduct amphibious operations however. In their first thrust towards Lae at Nassau Bay, a small objective enroute to Salamaua, 18 landing craft were lost to land a single battalion against negligible defenses. Never-the-less Nassau Bay was secured and used as a staging base for subsequent thrusts up the coast. The pressure exerted by the coastal advance was complemented by the Australian 15th brigade advance inland from Wau, about 30 miles inland from Salamaua. Unfortunately New Guinea’s rough terrain severely impeded the australians. The completely restricted terrain essentially forced them to utilize the few trails which constituted the only ground lines of communication toward the coast making their movements easily predictable to the Japanese and thus easy to defend against.

The Japanese established defensive positions along these approaches turning the Australians advance into a 75 day ordeal characterized by jungle knife fights and constant ambushes in the dense vegetation. The casualty numbers reflect the brutal nature of the war in the southwest pacific. Typically artillery is the principal means of killing the enemy however in the southwest pacific small arms were the King of battle and inflicted a third of casualties and artillery on 17 percent. This was in stark contrast to the European theater where artillery accounted for 57 percent of casualties and small arms only 20 percent.

The ground campaign did not go unsupported however. General Kenney was conducting his own aerial campaign to support the capture of Lae. In order to strike the major Japanese air base at Wewak he had an entire air base built in secret only sixty miles southeast of the Japanese at Tsli-Tsli. From there he was able to launch a devastating raid in August that resulted in roughly 125 Japanese aircraft destroyed on the ground in two days. That constituted three quarters of the aircraft of the Japanese fourth Air army and left the defenders vulnerable to further aerial attack which MacArthur would fully leverage to his advantage.

With Lae and Salamua isolated and weakened, the Allies closed the trap. From September 4th to the 6th the Australian 9th Division and 2nd Special Engineer Brigade landed eighteen miles east of Lae placing 7,800 troops on the Japanese doorstep. This was accompanied by the first allied american combat parachute jump of the war when the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment was dropped on Nadzab. The Paratroopers met no opposition and secured their landing with ease allowing a fleet of hundreds of C-47’s to ferry in the entire Australian 7th Division. General Adachi now had two whole divisions threatening his position and so decided to withdraw the bulk of his forces to Finschhafen due east at the tip of Huon peninsula . 8,000 Japanese Soldiers made the trek and a quarter of them died on the way through the dense mountain trails.

By September 16th both Lae and Salamua had fallen to the allies but MacArthur’s work wasn’t quite finished, he still needed to take Finschhafen itself in order to secure the route to New Britain. On September 22nd the Australian 9th Division landed in the port but met little immediate resistance. The Japanese had dug in on the ridgeline above the town. The effort to root out the Japanese in the vicinity of Finschhafen developed into a weeks-long slog that wasn’t fully resolved until the end of November but the job was done.

With New Georgia and the tail of New Guinea firmly in allied hands by the end of 1943 the conditions were set to begin the next phase of the Solomon islands campaign. In MacArthur's area General Walter Krueger, not to be confused with the SS officer of the same name, was preparing an amphibious task force to invade New Britain itself. In Halsey’s sector the I Marine Amphibious Corps was preparing to invade bougainville.