Episode 45: War on the Cold Periphery

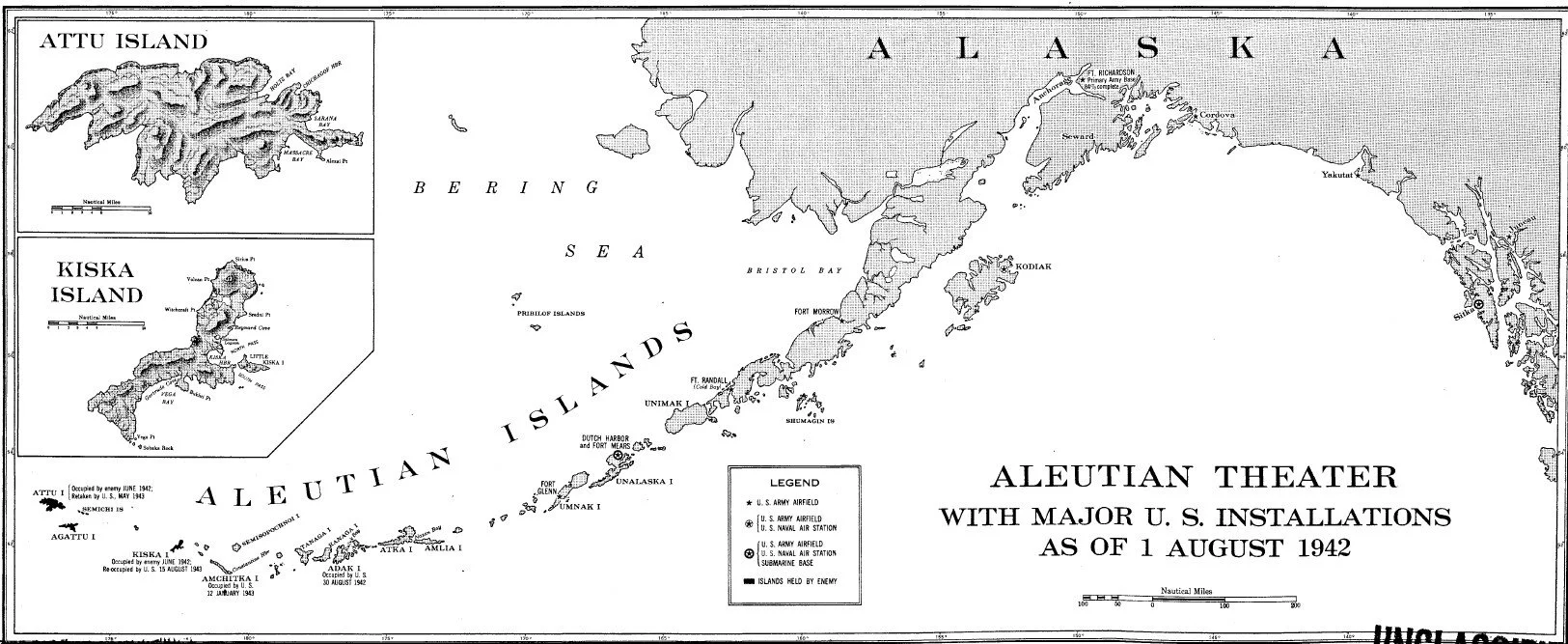

The strategic situation that resulted in the Aleutian Islands campaign is rooted in the same events that shaped the Southwest Pacific, and the Central Pacific which we have discussed at length beginning way back in episode 18 but to recap: in the wake of Pearl harbor the Japanese exploded across the pacific, seizing land in Southeast Asia, Indonesia, New Guinea, the Solomons, and the Central Pacific in order to forge a massive island perimeter around the western Pacific. The Aleutian Islands, stretching from the tip of Alaska more than a thousand miles westward toward Asia, represented what the Japanese saw as the key to defending their North Eastern flank. At their closest, the Aleutians come within only 650 miles of the Kuril Islands. In fact, Attu islands, the westernmost American island in the chain is closer to the Japanese Kurils than it is to the Alaskan mainland. A bit surprising considering that we usually imagine the United States and Japan as being separated by several thousand miles of open ocean across the breadth of the Pacific. Not that either of these island chains are particularly developed or well defended but they posed a threat none-the-less.

The islands themselves constitute yet another form of absolute misery, and maybe the most miserable fighting conditions we have yet discussed. Geographically the islands are the result of volcanism, with jagged shorelines and rapidly rising elevation consisting of volcanic cinder cones. Climatologically they are characterized by frequent cold rains, up to 50 inches a year, driven by warm water currents rising up from the equator along the eastern seaboard of Asia. Much like the northern british isles or Scandinavia is warmed by the gulf stream. This warm water makes the islands particularly foggy and brings frequent storms at sea. On land, the climate is too cold for any real vegetation, they are generally at the same latitude as London or Vancouver, so instead the islands are covered in a dense mass of muskeg, the regional name for peat moss, which forms a deep, sopping material. This combined with the uneven terrain could form invisible pits that men could disappear into. Though the weather was a constant headache for military planners, the Japanese held one advantage. Given that the prevailing winds are from west to east they had a better idea of what weather systems were bound for the islands and could better prepare.

The North Pacifica Area of the Pacific theater came into play almost immediately. The invasion and occupation of the Aleutians was to take place alongside the Japanese invasions of Midway, the gilberts, and the Solomon islands in their efforts to create an outer perimeter. The specific time for the occupation of Aleutians was uncertain at first but the Doolittle raid on Tokyo increased the Japanese awareness of the Northern flank and thus was made to coincide with the battle of Midway. Yamamoto believed that he could draw the US Pacific Fleet away from Pearl Harbor by demonstrating toward the North Pacific and using that as a distraction from his main thrust toward Midway. The plan was for Nimitz to then redirect his fleet south to prevent the capture of Midway and catch him in a trap. Yamamoto provided Vice Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya’s Northern Area Fleet with two small aircraft carriers, five cruisers, twelve destroyers, six submarines, four troop transports and various other support ships to achieve his goals.

Having cracked the Japanese naval code, Nimitz was aware of Yamomoto’s plan and acted to thwart it. The resulting battle of midway we already discussed in episode 25 but we did not discuss the force sent to deal with the Japanese diversion in the North Pacific. To deal with the Japanese threat to Alaska, Nimitz dispatched Rear Admiral Robert Theobald in command of Task Force 8. Task Force 8 had no carriers because Nimitz wanted those committed to the defense of Midway but it did consist of five cruisers, fourteen destroyers, and six submarines. Theobald departed Hawaii on May 25th 1942 with orders to defend Dutch Harbor, the largest, yet still small, naval facility in the island chain.

In early 1942 the Alaska Department had 45,000 men assigned to it with about 13000 at Ft. Randall, at the tip fo the Alaskan Peninsula all under the command of Major General Simon Bolivar Bucker, of later fame at Okinawa. Only 2300 men, not counting Army Air Force Personnel, were stationed in the Aleutian islands themselves at Dutch Harbor and Fort Glenn, about 70 miles further west. Total Air Forces in the region consisted of 44 bombers, both light and heavy, and 95 fighters under Brigadier General William Butler of the 11th Air Force. When Admiral Theobald arrived he met with General Buckner at Kodiak island and combined his forces with those of the Alaska Defense Command.

The first objective was to locate the enemy fleet. This task was handed to the 11th air force who were to patrol the waters surrounding the aleutians in order to locate, and then attack the enemy surface vessels beginning with his carriers. Their 23 PBYs were ideal for this task with their 400 mile range but would be stretched to their limit to cover the search area effectively. They would be substantially aided by the installation of RADAR on their aircraft which allowed them to detect not only enemy ships in the dense clouds, fog, and rain of the north pacific but also mountains and other land forms that could create navigational hazards.

On June 2nd they briefly detected the enemy fleet roughly 400 miles southwest of Dutch Harbor but poor weather and low cloud allowed Hosogaya to quickly disappear. The next morning, in conjunction with the Midway Operation, the japanese launched an aerial attack on Dutch harbor. At 0545 anti-aircraft gunners spotted 15 Japanese aircraft which proceeded to strafe the shore facilities. They did little damage and departed to the north but were followed five minutes later by four bombers which dropped a total of 16 bombs. This run did more significant damage destroying two barracks, four quonset huts, and killing 25 men. A third wave appeared shortly thereafter but missed its target. In total 15 fighters and 13 bombers participated in the raid but none were shot down. Intense anti-aircraft fire likely disrupted the Japanese’ attack however resulting in reduced loss of life.

On June 4th the Japanese launched another raid this time with greater success. At Dutch Harbor a combination of dive bombers and horizontal bombers managed to destroy four 6600 barrel fuel tanks for a total loss of over 20,000 barrels. They also desroyed part of the hospital, a barracks ship, as well as partial damage to a warehouse and an empty hangar. 43 Men were killed and a further 50 were wounded. Simultaneously Hosogya launched a raid on Fort Glenn on Umnak island. Here at least Army Air Force Aircraft were able to scramble and intercept the japanese raiders. Two Japanese aircraft were downed and the rest withdrew without delivering their payloads. As they receded into the fog bank, American radiomen tracked their transmissions and listened to the panicked voices desperately searching for their carriers. Those flyers never returned home and were forced to put down in the frigid ocean where they likely froze to death or drowned. The attacks of 3 and 4 June represented the only offensive action by the Japanese in the central or eastern aleutians. From then on all of their efforts would be concentrated on the far western end of the island chain.

As Admiral Hosogaya roamed the north pacific launching raids, American patrol craft continued to hunt and track him. The strain this put on the aircrews was immense however. As weather and enemy action attrited the force the remaining crews airmen were forced to adopt ever more grueling schedules, sometimes as long as 48 hours of continuous operations in absolutely dreadful weather. By June 4th only 14 PBYs remained operational. On June 7th the situation was dire enough that the AAF agreed to essentially pilfer all of its west coast patrol squadrons, sending four A-29s, four B-17s and six B-24s up to Alaska to augment the air forces already present.

Meanwhile, Admiral Theobald’s task force remained on station in the Gulf of Alaska in order to be in position to interdict any attempted landings on mainland Alaska or any major island installations. On June 5th he acted on reports of enemy activity in the vicinity of Dutch Harbor which he believed could be a landing force. In conjunction with this movement he instructed General Butler to attack the enemy vessels with all available aircraft. A flight of radar equipped B-17s reported landing hits on Japanese vessels but it was later determined that they most likely bombed a scattering of uninhabited islands. While patrolling in the vicinity of Dutch Harbor theobald missed the actual landings taking place at Attu and Kiska 600 miles to the west.

In the wake of the failure to seize Midway island and the loss of four aircraft carriers the Japanese fleet withdrew from the central pacific. Rather than withdraw the North Pacific fleet as well, Yamamoto instructed Hosogaya to attack the western aleutians to at least somewhat compensate for the loss of initiative in the central pacific and even dispatched two carriers to bolster Hosogaya’s forces. On June 6th 500 marines of the Japanese Number 3 Special Landing Party landed at Kiska and 301st Independent Infantry Battalion occupied Kiska. In fact, it wasn’t even clear to the Americans that anything had happened until June 11th when patrol craft spotted unknown vessels in Kiska harbor. In response, a continuous bombing operation was ordered. This proved minimally effective however as the PBYs were not well suited to bombing missions.

The only American presence on either island was a 10 man naval weather station on Kiska island, one of whom escaped Japanese capture in the initial occupation. The single sailor wandered the island for 50 days avoiding capture, eating grass and nearly freezing to death. After nearly two months of this hellish existence the man surrendered to the Japanese.

On June 12th the 11th Air Force launched a flight of liberators to bomb Kiska but due to the distance and the pilots unfamiliarity with the area it proved futile. Only three bombs found their targets but only incurred superficial damage. In return the Japanese managed to shoot one of the American aircraft down with heavy anti-aircraft fire. More bombing runs would follow but for the most part they proved ineffective and likely served as little more than a nuisance for the occupiers. A more determined effort would be needed to dislodge the Japanese.

In Mid June the Joint chiefs agreed that a concerted effort must be made to expel the Japanese from the Aleutians. Not so much because they posed a threat to American operations. An invasion of Japan via the northern route was never seriously considered and without Midway the outposts served little use for the Japanese. There remained some lingering concern for a Japanese invasion of the Alaskan mainland. Three different sightings of Japanese forces in Alaskan waters triggered a massive reaction from the United States to reinforce the Alaska Department. In 36 hours 2,300 troops were airlifted to Nome, the assumed objective of the suspected invasion. By mid-July, after observing Hosogaya’s fleet leaving the North Pacific military leadership felt comfortable that the threat of invasion had subsided and the additional troops were redeployed elsewhere.

Despite these concerns the primary reason for expelling the Japanese was pride. They were on American soil. The Joint Chiefs simply could not tolerate any occupation anywhere in America, no matter how distant or uninhabited. Attu and Kiska could well have been left to wither on the vine much as many other Japanese Pacific Garrisons with little effect on broader operations but in the early war these morale victories were just important as tactical ones.

To set the conditions for the recapture of Attu and Kiska Admiral Theobald and General Buckner set out to establish a network of air bases in the central Aleutians from which to launch bombing raids on the occupied islands and execute a strong attrition policy aimed at wearing down the Japanese garrisons. They needed to get air bases within 250 miles of the enemy and began reconnaissance missions to identify suitable locations. In the meantime, a submarine screen was established and proved effective, sinking one transport ship and one light ship during the first month. Several islands were identified that would serve as good air bases but Adak was determined to be the best for their purposes.

The first of these island air bases was occupied on August 30th when 4500 Soldiers seized Adak, 400 miles west of Umnak. Within two weeks an airfield was completed, a feat of engineering efficiency that the engineers would repeat again and again throughout the theater. On September 14th, the first bombing run of B-24s took off from Adak to raid Kiska, 200 miles west. This first bombing run struck three transport ships, sunk two minesweepers, and strafed three midget submarines. Not a grand haul but a good start.

For their part, the Japanese had not sat idle during the intervening period. In August 1000 more marines arrived on Kiska along with a 500 man laborer detachment and by November total strength on the island was about 4000 men. Total strength on Attu climbed to roughly 1000 men. The Japanese were counting on the winter months to ease the pressure from American strikes but the weather and relentless conditions would prove to be equally fierce opponents.

American forces continued to build over the winter months as well. By January of 1943 94,000 Soldiers were assigned to the Alaska Command thirteen more bases had been constructed on the Aleutian chain including Amchitka island, occupied on January 11th only 50 miles from Kiska. The ever encroaching American bases combined with Admiral Kinkaid’s, he had replaced Admiral Theobald in January, blockaid of Attu and Kiska resulted in those forces being almost completely cut off from resupply. Knowing they had to do something to support their increasingly isolated forces, Admiral Hosogaya led his Task Force consisting of four heavy cruisers and four destroyers to run the blockade. With him he brought three large transports laden with all manner of supplies for his beleaguered forces.

Admiral Hosogaya’s force met with Admiral Kinkaid’s blockaders on March 26th, 1943 resulting in the battle of the Komandorski islands. Keep in mind, the battle actually took place west of the international date line so technically it took place on March 27th, but by the reckoning of the American participants, who maintained Alaska, time it was the 26th. Admiral Charles McMorris formed his Task Force of six Vessels, two cruisers and four destroyers, in a picket line about 100 miles west-northwest of Attu island. His vessels were spaced at the customary six miles and making regular zigzags when at 0730, one hour before dawn, the lead ship, the USS Coghlin, made Radar contact at 24,000 yards. With the radar bearing the lookouts were able to identify three vessels but due to darkness were unable to confirm type. Admiral McMorris ordered his vessels to collapse the formation and increase speed to close the distance with the unidentified vessels.

At about 0750 the unidentified vessels turned left and headed north, almost certainly having spotted the American Task Force. There was little doubt left that these were Japanese ships. At 0803 Admiral McMorris radioed Admiral Kinkaid to inform him that they were pursuing enemy vessels and at 0820 at least nine vessels had been counted in the formation including both surface combatants and auxiliary ships. Soon after they positively identified two heavy cruisers among the Japanese fleet upon which Admiral McMorris later remarked “the situation had now clarified, but had also radically and unpleasantly changed.” It was now clear that the Japanese had the advantage in position and in strength, possessing a large overmatch in firepower against McMorris' one heavy cruiser and one light cruiser.

Despite the seeming disadvantage Admiral McMorris decided to press on and target the auxiliary ships. He hoped that by doing this he could bring the transport ships within range before the enemy cruisers were in position to stop him. He thought he might be able to get the Japanese to split their forces if one part were to cover the retreating merchantmen while another screened their withdrawal. By 0840 Admiral McMorris’ Task Force Mike was finally in formation and cruisering north by northwest with the destroyers Bailey and Coghlin leading, followed by Richmond and Salt Lake City, recently refitted after the battle of Cape Esperance, 1000 yards behind. Two her starboard rear quarter trailed the destroyers Monaghan and Dale. Battle was about to be joined.

Opposite them the enemy vessels cruised southeastward with the two heavy cruisers in the lead followed by two light cruisers and two destroyers. At 0840 the lead Japanese cruiser opened fire on the Richmond at 20,000 yards. The Richmond and Salt Lake city immediately opened fire in return. Japanese gunnery proved adept and they began landing shells very close to the Richmond after only salvo, so close that her skipper believed they had been struck amidships and dispatched damage control teams. They found that only a guy wire had been cut between smokestacks. The return fire proved accurate as well. An 8 inch shell from Salt Lake City was observed impacting one of the enemy cruisers starting a short lived fire.

Despite the early success, McMorris felt he was at too much of a disadvantage and ordered the Task Force to withdraw. The gun duels continued for about 20 minutes with shells crashing all around his task force, oftentimes within two or three hundred yards. Close enough that crews could feel the percussion blast as the rounds impacted the water. At 0903 the Richmond left effective range and ceased fire. The Salt Lake City was still in range however and at 0907 one of her 8 inch shells struck home again, this time sending thick black smoke billowing out of the Japanese vessel. Unfortunately, she would herself be struck by an enemy shell three minutes later when a Japanese round landed in her aft below the waterline. Though the damage was not critical it had ruptured oil tanks and exploded behind the aft engine room bulkhead.

The battle proceeded in much the same manner for the next three hours after the initial gambit to catch the cargo ships unprotected failed. The American ships would attempt to keep the Japanese heavies at arms length as the Japanese seemed willing to partake in a long range artillery duel rather than close with their destroyers as they often did in the south pacific. This may have been because they were themselves ferrying troops and supplies and Hosogaya did not want to expose them to undue threat. In the end the Japanese chose to retire rather than force a decisive result, perhaps due to damage inflicted by American gunners or due to depleted ammunition stocks after several hours of constant gunfire. Either way, the engagement resulted in a tactical draw but an operational victory for the US Navy. After retiring Hosogay was unable to relieve his forces on Attu and Kiska so from then on they could really only be resupplied by submarine. After his failure to penetrate the American blockade, Hosogaya was relieved of command.

With the islands effectively cut off from regular resupply the time was ripening for their recapture. Of the two, Admiral Kinkaid and General Buchkner determined Kiska to be the more important because it had a better harbor and an airfield. Attu, on the other hand, was believed to have a significantly smaller garrison and lay along the sea lines of communication to Kiska allowing them further isolate it. By early March Admiral Kinkaid had identified that he lacked the shipping to conduct a large enough landing to take Kiska anyway.

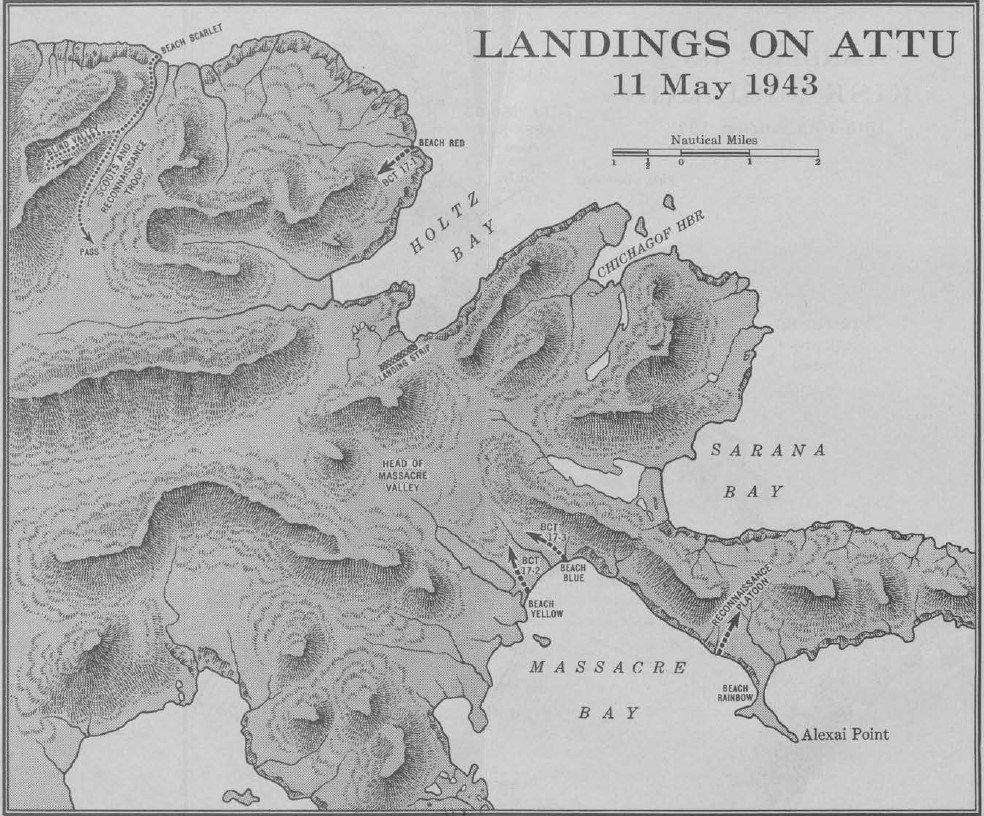

On April 1st, 1943 the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the Attu Operation, codenamed SANDCRAB. Though the number of Japanese defenders was originally estimated at 500 men, intelligence soon inflated that number to at least 1300 but as many as 1600 men causing General Buckner to request additional forces. Initially he had only allocated a single regiment to seize the island but now determined that an entire division would be neccessary. The Western Defense Command found the 7th Infantry Division in training near San Francisco and selected them for the Attu landings. By the end of the month they found themselves at Fort Randall at Cold Bay Alaska. Having been stationed in California they were not acclimated to or prepared for the cold of Alaska and lacked proper equipment. The planners for SANDCRAB were confident the battle would be over within three days however so the effects of lacking proper clothing would be minimal.

To support the land force Admiral Kinkaid assembled his available forces which included three battleships, an escort carrier, three heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, 19 destroyers, as well as tenders, oilers, and transports. The 11th Air Force brought 54 bombers and 128 fighters to the operation.

The invasion was initially scheduled to begin the morning of May 4th but bad weather forced delay after delay. It was more than a week before the weather had cleared sufficiently for the landings to take place. But on the morning of May 11th, 1943 American forces were finally returning to Attu.