Episode 46: Battle for the Backwater

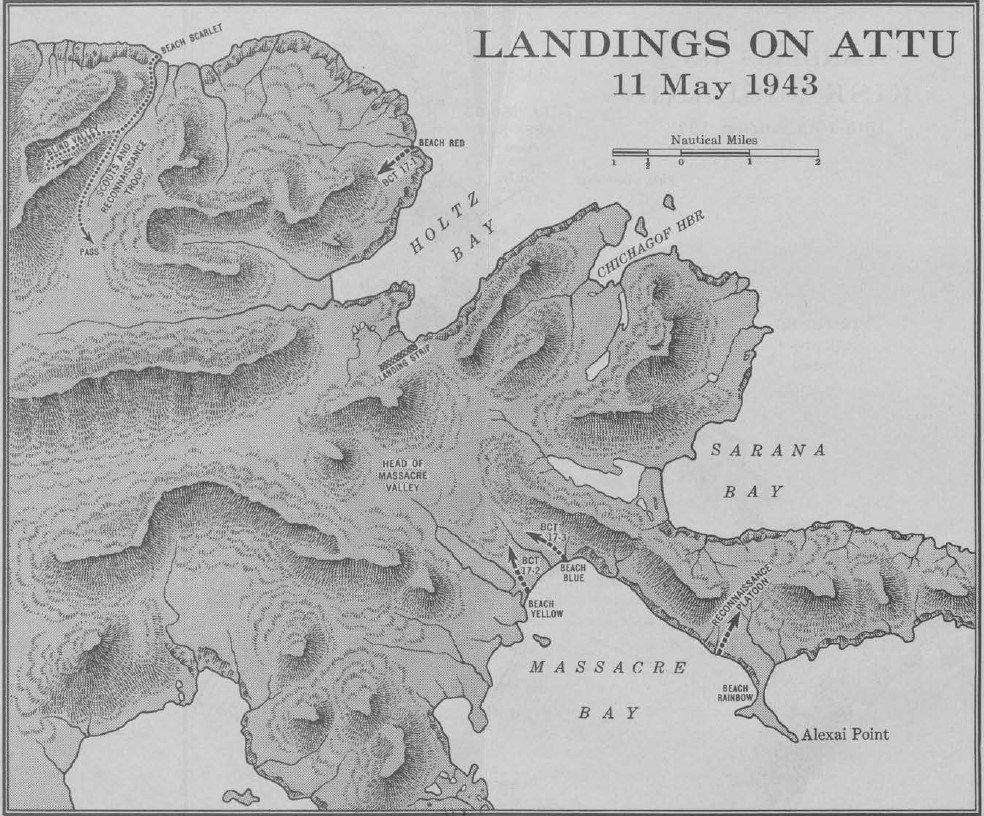

On the morning of May 11th, 1943 11,000 troops were staged at sea for the assault on Attu Island. The first men ashore were those of the 7th Scout Company who paddled to the beach before dawn from their submarines.. At 3 in the morning the first first troops from Narwhal waded in followed by the men from the Nautilus at 0500. The remainder of the company were much delayed when their transport, the destroyer USS Kane, could not find the landing beach for several hours. They came ashore, amidst the frigid pre-dawn surf, at SCARLET beach, nine miles north-west of the overall objective: Chicagoff harbor. Their first task after landing was to determine whether the beach was suitable for a larger landing with more troops and equipment. Theirs was the northern and westernmost landing point.

The eastern half of Attu island is shaped a bit, if you really squint, like a clover turned on its side with three peninsulas emerging from the landmass towards the northeast, east, and southeast. The primary settlement and location of Japanese defenders was on the northern tip of the central peninsula where Chicagoff harbor lies. The other piece of valuable real estate lay at the southern tip of Holtz Bay where an airstrip had been constructed. Rather than assault Chicagoff harbor or the airstrip directly, landings would take place at four locations, two in the North at RED and SCARLET beaches, and two in the south in the mouth of Massacre bay at Yellow and Blue beaches. The idea was to land in relatively unopposed beaches where uncontested supply lines could be established to approach the Japanese defenders from the rear.

Unopposed at SCARLET Beach, the scouts quickly moved inland where they were to assess their second objective, the feasibility to approach Holtz bay from the north. At noon the 7th Division’s reconnaissance troop came ashore at SCARLET beach and joined up with the scouts forming a provisional battalion. By roughly 1500 the provisional battalion had formed up the head of the valley leading to Holtz Bay and were nominally prepared to support the landings at RED beach but after a full day of trudging through rough terrain in dreadful conditions the men of the provisional battalion were absolutely spent.

At 9:30 in the morning eight landing craft came ashore at beach RED. They carried another reconnaissance element composed partially of Aluet scouts. Their task was to determine the suitability of beach RED for a larger landing. They never got word back to the high headquarters however so it was up to USS Bell to ride in close to report on surf conditions. Determining them to be calm enough to debark men and supplies the 1st Battalion 17th Infantry, which had been waiting on word on whether to land at SCARLETT or RED, went ashore at RED. Having spent the day waiting for word from the scouts it was already 1500 by the time a decision had been reached and men began to be put ashore. Given the awful weather conditions many landing craft became lost in the fog and destroyers had to patrol the area off of Holtz bay to gather up errant landing craft. It wasn’t until well after dark that the final troops were landed.

As soon as the men of the 1- 17 infantry came ashore they were greeted by a rock studded beach and a 200 foot escarpment that overlooked the whole landing zone only 75 yards from the high tide line. Identifying this piece of key terrain the men began moving inland to seize it. Though they found no resistance at the beach they soon began taking japanese fire at 1800 from hill “X”. Unable to overcome both the conditions and the enemy 1-17 halted short of the hill.

As men were wading ashore in the northern beaches the 2nd and 3rd battalions of the 17th infantry were busy landing in the south on the shores of Massacre Bay at Yellow and Blue beaches. After landing they began moving inland toward their first day objectives and themselves came under enemy fire at roughly 1900. 3-17, whose objective was Jarmin pass, failed to dislodge the defenders. Still, by 9:30 pm 3,500 men of the 7th Infantry Division had landed, 400 at Scarlet Beach, 1100 at Red Beach, and 2000 between Blue and Yellow Beaches including General Brown, the Division commander. All things considered, he would not have been considered, well off the mark if he thought the situation was well in hand and the Japanese would be swept off the island in a only another day or two. After all, he had a whole other regiment prepared to land the next day and the 4th Infantry Regiment held in reserve by General Buckner should he need it.

As bad as their losses were on the first day, they may well have been worse if it were not for the unrelenting fog that forever shrouded the island. Despite lingering off the shore for hours the Japanese had no idea an invasion was underway until 3:00 in the afternoon. This meant they only began emerging from their cave shelters after the Americans were already beginning to land at their primary assault beaches. Col Yasuyo Yamazaki, the defending garrison commander, had no intention of defeating them at the water's edge though. His men had dug defensive positions in the high ground about 3-4 thousand yards from the waterline.

The next day the weather was just as awful but the men on land were able to spot naval gunfire and aviation support was brought to bear. The 14 inch guns of the USS Pennsylvania were fired on targets in the west arm of Holtz bay, just south of Hill X. Following the naval bombardment, at just before noon, aerial bombardment commenced against targets in the same area. The bombers met heavier than expected anti-aircraft fire so additional 14 inch naval gunfire was requested to suppress the AA positions. This time the USS Idaho let loose 48 rounds high explosive rounds. It's unclear whether the positions were destroyed in the bombardment but Idaho would be busy again later in the day.

In the north 1-17 pressed their assault on the japanese defender in the vicinity of Hill X and with the help 200 14 inch rounds from the USS Idaho managed to take the crest of the hill. Though the defenders still held the reverse slope and attempted several times to throw the Americans off the top progress was being made. While they were advancing reinforcements from the 3rd battalion 32nd infantry were landing on Beach Red. Their landings, while interrupted by artillery fire and abysmal conditions, managed to get a whole additional battalion on the ground.

The southern elements experienced problems of their own on May 12th. For one, the thick mud and muskeg made trucks almost useless a they bogged down almost immediately. This forced commanders to assign a disproportionate number of men to labor duties rather than to taking the actual objectives. So much so that the landing force commander requested that Admiral Rockwewll land his reserve troops to help with the extra labor demand. Rockwell was a bit nervous about this as there were still transports unloading in the Massacre bay and feared submarine attack. Once the transports were emptied he released the reserves but in that time a torpedo was spotted heading toward the Pennsylvania. Luckily, evasive action succeeded in avoiding being struck.

Farther inland the going was slow against the entrenched defenders overlooking Jarmin pass. Frontal attacks proved fruitless in gaining ground while casualties mounted. After several attempts little progress was made and the forward line of troops had hardly changed on the second day. Both battalions, the 2-17 and 3-17 had been pinned down by effective machine gun fire as they attempted to dislodge the defenders from the highground. That night the first casualty reports came in. In two days of fighting 44 officers and men had been killed.

The 13th transpired much as the previous day had. 2-17 and 3-17, now aided by 2 battalion 32nd Infantry, continued to beat their heads against the wall in the vicinity of Jarmin pass and at the end of the day the forward line of troops had changed little. In the north 1-17 IN held onto Hill X and beat back several Japanese attempts to shove them off the hill top but themselves made no further progress.

Overnight shelling had slowed 3-32 IN’s unloading progress but by days end they were in the fight as well, moving up to support 1-17 IN. There was some progress made in establishing artillery positions at least. Japanse fires had prevented the artillery in the north from establishing and offering fire support to 1-17 IN but with the aid of naval gunfire the Japanese guns were silenced long enough for the American artillery to occupy firing positions.

On May 14th General Brown decided to try to make a combined attack on Jarmin pass from north and south. The provisional battalion, which had landed at Scarlett beach and had been held up in the hills behind Hill X was to make its way south and attack Jarmin pass from the rear. 1-17 IN and 3-32 IN were to finish driving the japanese from Hill X and support the provisional battalion. The southern forces were ti continue their assaults up the massacre valley. Unfortunately none of this happened. The provisional battalion remained fixed and 1-17 IN was unable to finish the job on Hill X. So yet another day passed with essentially no progress being made. Despite naval fire support and aerial bombardment the Japanese remained stubbornly in place. General Brown was beginning to consider calling on the reserves held by General Buckner. Three days had passed and none of the division's objectives had been realized.

The 15th offered frustrations like those of the past several days. Unloading activities in the northern sector at Red Bech remained frustrated by beach conditions as well as japanese indirect fire. Attacks at Hill X and up the Massacre valley were launched late due to thick fog reducing visibility to mere feet. There was one bright spot however. Around 100 the fog lifted and it became clear that the enemy which had been blocking the provisional battalion had withdrawn to Moore Ridge which runs between the northern and eastern cloverleafs. With nothing to stop them the provisional battalion advanced on the ridge and called for close air support to help suppress the defenders.

The relatively clear conditions proved to be as much of a hindrance as an asset however. The long lines of visibility allowed the defenders on Moore Ridge to deliver effective fire on the advancing Americans who were quickly fixed. To make matters worse some of the close air support dropped their bombs on friendly positions. The provisional battalion would halt short of Morre Ridge by day's end. In the southern sector essentially no progress was made once again.

At 1140 AM another torpedo attack was spotted and successfully avoided but the pressure was mounting to withdraw the ships from the bay. That afternoon General Brown went aboard the Pennsylvania to conference with Admiral Rockwell. He pleaded for more men and construction equipment arguing that all available forces had already been committed and were insufficient to secure the island. The comments from the meeting were forwarded to Admiral Kinkaid, General Buckner and General DeWitt back on Adak. Kinkaid was particularly concerned with allowing his ships to continue to linger off the island. There were reports of a Japanese fleet approaching to drive off the invasion force. Given the lack of progress on the island and the looming threat of the Japanese fleet the commanders agreed it was time to find a replacement so General Brown was sacked.

On May 16th, after five days of fighting in miserable semi-arctic conditions the tide finally began to turn. The Provisional Battalion continued its advance on Moore Ridge and managed to seize a foothold at the center of the crest allowing them to leverage fires on the entire length of it. At the same time 1-17 IN and 3-32 IN found that the enemy had withdrawn from their sector as well and so moved to secure landing sites near Moore Ridge in order to significantly reduce the length of their supply lines.

In the Southern sector a similar change of fortune had occurred. The Japanese defending Jarmin pass and blocking the Massacre valley had themselves withdrawn allowing the Americans to advance northward for the first time since they landed. These withdrawals in the northern and southern sectors did not mean the Americans advanced uncontested however. There were still numerous small engagements and observers continued to call in naval gunfire as well as close air support. Naval aviation from the USS Nassau as well as army aviation carried out sorties throughout the day on various targets across the island. B-24s were also used to resupply forces in the vicinity of Beach Red.

At 10:00 in the evening Maj General Eugene Landrum arrived and assumed the role of Landing Force Commander. He took command at an auspicious moment. The night before the Japanese had chosen to withdraw to an inner cordon around the town of Attu itself, at the eastern tip of the eastern cloverleaf on the shore of Chichagof harbor. General Brown’s request for reinforcements was also headed so more men would soon be arriving to relieve those who had already been in the cold, wet miserable conditions for the better part of a week. The fighting was far from over however. The advance on Attu and Chichagof harbor would be grueling. On 17 and 18 May 1-17 IN and 3-32 IN would clear the remainder of the defenders around Holtz Bay but the number one cause of casualties was not enemy fire but rather frostbite by a ratio of two to one. By the end of the 18th the northern and southern forces were able to link up in Jarmin pass.

Progress would continue at its glacial pace for the next five days where fighting was characterized by exhausting advances on japanese machine gun nests dug into hillsides or ridgelines in wet or even snowy conditions. The higher the elevation the worse the weather where driving snow and biting wind were just as much a hindrance as the actual enemy. The rough terrain also made positioning artillery difficult. In many places the ground was too rough but where it was flat enough the ground was generally a soft muck that was best avoided.

On May 27th American Forces had reached the town at Attu itself but the Japanese continued their dogged resistance. An area known as the fish hook region was captured that day when five companies climbed a 60 degree incline to enter and clear it in detail at extremely close quarters and savage fighting repeatedly using grenades, rifle butts, and bayonets.

On the 29th the defenders would launch a massive counterattack of roughly 700 to 1000 men down the Chichagof valley in an attempt to take Jarmin pass and wreak havoc in the American rear area. They threw everything they had left into the effort and quickly overran the 3-17 IN defensive positions assaulting the battalion as well as the regimental command posts in the lowland near Sarana Bay. They managed to cut all the telephone wires in their path, severely impacting command and control in the immediate area as well. General Landrum was forced to commit the division reserve to halt and repel the counterattack. The reserves were successful in stopping the advance killing over hundred of them while scattering the rest in disorganized bands that continued to harass American forces and had to themselves be cleared in detail.

The next day the counter attacking force made one last thrust that was easily halted. 3-17 IN killed at least fifty of them in repelling their assault. Meanwhile the main effort continued to drive on Chichagof harbor and made it all the way to the waterline. By this time the Japanese forces were spent however. The counterattack had consumed nearly all of the rest of his combat power and despite some initial success it proved fruitless. Though some small pockets had to be cleared out the fighting was all but over by May 30th. There were some aerial attacks on the ships supporting the invasion but they proved ineffectual as well.

All told, American forces suffered 549 men killed and 1,148 wounded along with 2,100 non-battle casualties, mostly trenchfoot and cold weather injuries, out of the total attacking force of 15,000. A total of 2,351 Japanese corpses were found though its presumed several hundred were either never recovered or were buried by their comrades during the battle. Only 28 Japanese prisoners were taken. Following the battle the engineers determined that the site of the airfield near the east arm of Holtz bay was rather poorly chosen and so abandoned it to build a new airfield in a more advantageous location.

The Attu operation, though largely forgotten today, was a uniquely miserable campaign. American Soldiers had to face a tough, determined enemy dug into difficult terrain in the most miserable weather imaginable. For three weeks they suffered biting cold, fierce winds, driving rain, and even wet snow at times. The Japanese fought with their characteristic tenacity, engaging in brutal hand to hand combat and fighting to the last man. All of this for a tiny spit of nearly inhospitable land on the far northern periphery of both the United States and Japanese empires.

The battle did yield some good data for American planners however. It was clear from battle damage assessment that naval gunfire was not particularly effective at destroying deg in fighting positions. It was however, extremely effective at suppressing the enemy. The few captured Japanese along with documents discovered attested to the devastating effect naval gunfire could have on the morale of theSoldiers it was directed against, hence its major suppressive effect. It's hard to man a machine gun or dial in an artillery piece when a 1400 pound slab of high explosive is detonating anywhere near you and you know more is coming your way. It also had a demonstrable positive effect on friendly morale. I guess something about the roar of 14 inch guns flying toward the enemy was comforting to the infantry. When combined with aerial support, naval gunfire could provide sufficient cover to allow friendly units to maneuver relatively harassed and with only minor casualties. Due to the extreme nature of the weather and terrain enormous amounts of ordnance were used for relatively little material destruction. Naval vessels from destroyers to battleships fired hundreds of rounds each to achieve suppression. The infantry still had to fight through and clear their enemies out.

One small luxury Soldiers on Attu received was hot food. Since the supply lines from beachhead to the forward line of troops was so short for most of the battle, landing craft were able to deliver two hot meals a day for 1,200 troops consisting of coffee, coco, beans, and chili. Obviously not every Soldier was able to enjoy the simple pleasures of a hot meal, especially those who were farther from the beachheads, but 2,400 hot meals a day is nothing to sneeze at. In cold wet conditions like those on Attu a simple hot meal can go a long way to improving a man's fighting spirit.

The Battle for Attu ended up being one of the most grueling the US military would fight in the entire war. In terms of raw numbers it cost 71 American casualties to inflict 100 on the enemy, second only to Iwo Jima in exchange rate. In light of that fact its unclear to me how to judge General Brown. Its true that after six days of fighting he had achieved remarkably little but he had invaded an incredibly rugged and unforgiving island against a prepared and motivated enemy. Sure, General Landrum began seeing success almost as soon as he took command but to me that just seems like bad luck on Brown’s part. The Americans weren’t the only ones suffering from the extreme sub-arctic conditions ono the island. After six days of relentlessly, aerial, naval, and infantry assault the Japanese must have been exhausted. Sure, they had beaten back numerous assaults but we have to assume that they sustained heavy casualties and had expended significant ammunition in that time. By the time Brown was thrown out and Landrum brought in the Japanese probably had little left to throw at the Americans and thus withdrew to a tighter perimeter with shorter supply line from their headquarters in the town of Attu. Had Brown been left in charge for another 48 hours his fortunes would certainly have turned around just like they did for Landrum. Its also hard to say what he should have done differently. Attu had very limited landing beaches and even more limited avenues of approach. Even if the island were dry and the weather pleasant it would have been a nightmare to assault. Add in snow and rain and that deplorable muskeg and your problem are only compounded. Given all of the I think history should be kind to General Brown. There was little else he could have done with the situation he was handed and impatience on the part of his leadership led to undue embarrassment for him.

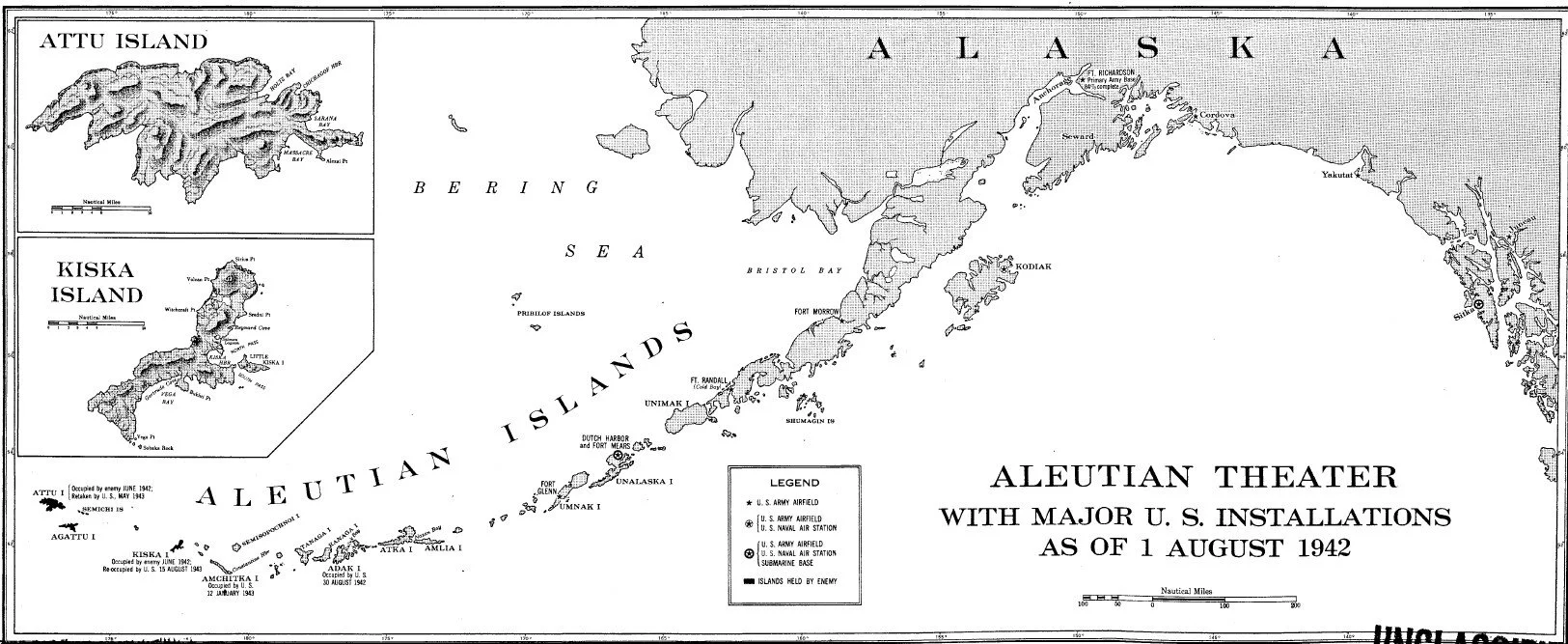

Having secured Attu and getting a functioning airfield operational by June 9th, it was time to prepare the invasion of Kiska. Admiral Kinkaid and General Charles Corlett, the ground forces commander for Kiska, did not want this invasion to suffer the same problems and set back as that on Attu so made a few corrections. First, they made sure they were outfitted with proper cold weather gear and footwear. Intelligence estimated the Japanese garrison at about 10,000 men, four times the number present on Attu so significantly more troops, roughly 30,000 american and 5,500 Canadian, were assigned to the invasion. In addition, the island was subjected to significant pre-invasion bombardment.

In the time between the occupation of Attu and the landing in August 424 tons of bombs were dropped on the island by the 11th Air Force and 330 tons of shells were lobbed into it from the sea.

The pilots flying over Kiska did notice a distinct lack of activity however. Two possible explanations were offered, either the Japanese had evacuated the island or they had taken to the hills to conduct a defense in depth. American planners decided to carry out the invasion anyway. If the Japanese were still there they would need to be rooted out anyway. If they were not then the landing forces would still get valuable experience in conducting a full scale rehearsal of an amphibious operation.

On August 15th 1943, over a 100 ships assembled off the western coast of Kiska. Luckily for the invasion force the usual dense fog had lifted and relatively calm, clear conditions prevailed during the landings. The Soldiers did not encounter any resistance as the unloaded and by 1600 6,500 troops had debarked. For the veterans of Attu this was not reassuring. They had seen a similar lack of activity at the beaches in the previous operation and expected to encounter resistance when they began scaling this ridgeline along the spine of the island.

As the Americans and canadians continued to unload and move inland they would not encounter any Japanese resistance for the duration because they had in fact invaded a desert island. The Japanese, to U.S intelligence great embarrassment, evacuated two weeks earlier. Knowing that the island had effectively been cut off after the fall of Attu, Japanese leadership elected to undertake one mass movement to get all of their troops off the island. On July 29th they brought in a fast moving force of cruisers and destroyers, loaded up all 5,000 men on the island and left, apparently without a trace because they were never detected by American aircraft or ships.

The total lack of defenders did not mean the invasion was a bloddless affair however. 21 Soldiers died in a friendly fire incident and 121 casualties were sustained either to injuries or cold weather. The navy suffered 70 dead and wounded when a destroyer struck a mine. All told, 313 casualties were sustained in the operation until August 24th when General Corlett declared the island secure.

With Attu and Kiksa both firmly back in American hands the Alaskan theater and the far north pacific quickly faded in terms of relative importance and priority. Both of the objectives of the campaign, to remove the northern approaches from contention, and to drive the Japanese from American soil, had been achieved. An invasion of Japan via the northern route was never seriously considered but that didn’t mean the Japanese didn’t defend against it. Despite the number of troops assigned to the Alaska theater dropping from a high of 144,000 to 63,00 the 11th Air Force continued to harass the Japanese in the Kuril islands, serving as an ever present reminder that American bases were only a few hundred miles away in the Aleutians and forcing them to maintain a significant defensive force there including one sixth of all of their air strength.

Though oft forgotten as a backwater campaign the battle for the Aleutians did have a tangible impact on the greater war effort. For one, considerable Japanese naval strength was frequently diverted to the North Pacific area. The invasion of attu occurred just before the invasion of New Georgia in the Solomon islands. The Japanese had dispatched their 5th Fleet from Truk in order to reinforce the North Pacific in the wake of losing Attu. This meant significantly less combat power was available to support the defenders in the Solomons, which one could argue, was the more important theater.

In the end the Aleutian Campaign is something of a curiosity in the second world war. Over its roughly 18 months there was only one major naval battle and one major land battle. Its strategic aims were modest, simply to cut off a northern invasion route that was questionable to begin with, and reclaim a couple of uninhabited island on the extreme edge of civilization. Once completed the campaign’s relevance evaporated and was quickly forgotten about for the much more consequential operations taking place in the Solomons and in the Mediterranean, Operation husky, the allied invasion of Scicily would begin on June 9th remember. It’s no wonder the Aleutian campaign is regarded as a forgotten backwater campaign when enormously impactful options were taking place at essentially the same time.

That in no way reduces the valor or heroism of the men who fought in the aleutians however. They did what their nation asked of them and endured conditions rivaled in no other theater. Their fight, though forgotten and eclipsed deserves to be remembered and appreciated.