Episode 47: Closing the Vice

At the very end of 1943 the campaign to isolate rabaul was proceeding apace. The campaign that had started in August 1942 with the landing at Guadalcanal had seen the seizure of the remainder of the Solomon islands and a parallel campaign up the New Guinea Coast. By December of 1943 axes of both of those advances converged at the Bismarck islands, specifically at Cape Gloucester on the very western tip of New Britain, the same island on which Rabaul is situated. Once Cape Gloucester was taken MacArthur would finish the encirclement by capturing the admiralty islands. The assault on Cape Gloucester would consist of two landings, the first at Arawa, on the southern coast, and at Cape Gloucester itself, on the northern coast of New Britain.

In September 1943 MacArthur issued the order to prepare the invasion of New Britain under the auspices of Operation Dexterity. Though there was some debate as to whether an invasion of New Britain was necessary the advocates for invasion won, arguing that it was critical to secure the sea lines of communication through the Vitiaz Strait between New Guinea and New Britain. They also wanted to secure the Airfield at Cape Gloucester to increase the range of allied aircraft and further isolate Rabaul.

Arrayed against the allies were the 15,000 troops of the Japanese 17th division under General Iawo Matsuda. The 17th Division was not a crack force however, instead it was a hodgepodge of units that had just sort of been stuck together, 10,000 of whom were actually located in western New Britain and arrayed to defend against the coming allied landings. Their rag-tag nature did not ease their difficulties in preparing defensive positions. For one, the weather and vegetation made simple survival difficult. Second, for two months before the allies actually invaded they bombarded Arawe and Cape Gloucester mercilessly, the 5th Air Force dropping over 2,000 tons of high explosive.

The landing at Arawe and the general seizure of western new Britain was assigned to General Walter Krueger’s Alamo Force, which caused some consternation with General Sir Thomas Blamey, the Australian who was nominally in charge of all allied ground forces in the South West Pacific who MacArthur simply cut right out of the equation. On Dcember 15, 1943 the first allied troops went ashore at Arawe. The 112th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division encountered no resistance in the landing and set to constructing a torpedo boat base. In the days immediately following the landing the japanese launched air raids against the beach head but it would not be until the end of the month that Japanese ground troops would arrive in an attempt to dislodge the invaders. General Sakai dispatched an infantry battalion and after several days of intense fighting the Americans, reinforced with tanks and additional infantry, pushed the Japanese back. By early January 1944 Arawe was entirely in Allied control, suffering 118 killed and 352 wounded for 300 Japanese killed. Meanwhile the main landing at Cape Gloucester had come in on December 26th and started soaking up most of the Japanese’ attention.

Like nearly every battlefield in the Pacific, Cape Gloucester was important for its airfield. Situated only 370 miles from Rabaul it not only threatened the Japanese Army headquarters it also essentially gave control of the straits between the Solomon Sea and the Bismarck Sea to the Allies. Early in the morning of December 26th the men of the 1st Marine Division were aboard ship waiting to disembark on their first amphibious assault since Guadalcanal. As they waited aboard ship they must have heard the roar of allied aircraft and bomb blasts echoing from the island. A veritable Air Armada had been assembled to bombard the landing site and provide air cover for the landing force. 14 squadrons consisting of nine bomber and five attack squadrons were tasked with reducing the Japanese positions prior to the landing in addition to five fighter squadrons tased with maintaining air superiority, an important role considering the largest Japanese air base in the South Pacific was only a few hundred miles away and on the same island.

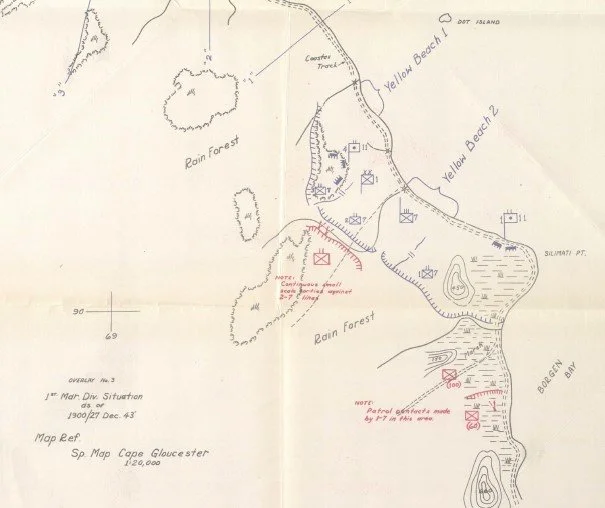

As dawn broke at 6:30 AM on the 26th the marines saw the imposing figure of Mt. Talawe. It brooded over the waiting troops, its lush slopes imposing and ominous. The roar of aircraft was soon joined by the cacophony of naval guns prepping the beach with shells. An hour later they would be hitting the beaches after navigating through the coral barrier that lay about 700 yards off shore. Two beaches, Yellow 1 and Yellow 2 were selected by aerial reconnaissance for the initial landing, both on the eastern coastline of the Cape. After landing, the marines would close the 1000 yard gap between the landing zones and advance on the Airfield from the southeast.

The coordination of aerial and naval bombardment with the shore approach was the best they had ever seen, recounted many of the participants in the invasion. When the first marines hit the beach at 0748 the Japanese had not even had time to recover from the shelling and the men of the 7th Marines went ashore nearly unopposed. The initiative gained after the preparatory bombardment was never lost during the first day and marines continued to stream ashore with the division commander landing and establishing a forward command post around 10:30. What resistance was encountered the first day was quickly swept aside and a Japanese Aerial attack on the landing craft that occurred about 1:00 in the afternoon was repulsed by the dedicated air cover. 59 Japanese aircraft were shot down in the aerial melee that followed. The worst of the Japanese casualties inflicted in the attack occurred when a group of low flying Japanese bombers flew through a formation of B-25 causing American AA gunners to fire on the whole group, Japanese and American aircraft included. Two B-25s were shot down in the confusion by allied rounds.

At the same time a diversionary landing was taking place at Green beach on the western shore of Cap Gloucester. Here again there was essentially no Japanese resistance and by 10:00 the 2nd Battalion 1st Marines had secured their objectives for the day. By evening fall they had established a perimeter and cut the coast road preventing the defenders from easily transferring troops. When word of the landing reached the headquarters of the Japanese 53rd Infantry Regiment they dispatched two companies in an attempt to bottle up the invasion force but it would take two days for them to actually make contact. By then the marines were too well established and they had no hope of removing them. They would engage in a series of smaller skirmishes to little effect. On January 13th the 2nd battalion 1st Marines would roll up their position and join the main body in the vicinity of Yellow Beach.

By the end of the 26th the entirety of the Yellow beachhead had been seized and secured by the 7th Marines and just over half of the LSTs cargo had been unloaded/. In addition, large amounts of Japanese stocks and stores had been captured along with artillery pieces and documents containing vital intelligence about Japanese positions and plans. A total of 50 defenders had been killed along with two taken prisoner for 21 marines killed and 23 wounded. That night the Japanese made their customary counter-attacks under cover of darkness which characteristically proved more devastating to their own forces than to their enemies.

The morning of the 27th opened with a Japanese counterattack on the 7th Marines right flank. It was only the prompt arrival of an artillery battery fighting as infantrymen that prevented the Japanese from overrunning the Marines’ positions. It was also on the morning of the 7th that another assault began, that of mother nature. The day of the 26th had been unusually calm and sunny but on the 27th the skies turned black and began to roil, the monsoon had arrived. Shortly after the storm clouds appeared on the horizon sheets of torrential rains began to fall that would last for weeks. Water and humidity became an ever present enemy. The remainder of the battle would be fought this way, in the following thirty days there would only be twenty seven hours of sunlight.

The constant heat and humidity turned everything to decomposition including rifles and tanks as well as rations and human bodies. A green slime seemed to take hold on everything and water permeated everything, finding its way into even the best sealed containers. The frequency and weight of the rainfall made small drainage ditches turn into torrents in matters of minutes. The volume of water flowing off the island could change the course of streams and creeks overnight and wash anything in their new path. During artillery barrages enormous mangrove trees could dislodge from the sodden soil and come crashing down on top of AMerican or Japanese fighting positions, crushing those who lay in its path. Twenty five marines died in exactly this way over the course of the battle and surely as many Japanese met the same fate.

The wet tropical conditions also made the island home to critters and creatures of all description. Poisonous flying insects, foot long centipedes that left red irritated tralis on the skin if they made direct contact, and twelve foot long constrictors abounded on the island. It was a veritable Jurassic park in which horrors of all kinds lurked in its dark depths, the least of whom being the Japanese. The vegetation grew at an incredible pace too. Enormous fronds seemingly growing in mere days and then rotting away nearly as soon as they appeared. The entire jungle was a roiling mass of flesh, vegetative and animalian. It consumed everything, equipment, ammunition, rations and worst of all: men. In this verdant hell the marines and Japanese would fight a slow, slogging, battle of flanking maneuvers and slugging matches for supply dumps.

The lack of Japanese resistance encountered on the first day would not persist. Following the overnight counterattacks and the morning assault the Marines would themselves have to go back on the offensives and clear the defenders out. The 53rd Infantry had built a series of bunkers from which to defend the airfield and they forced the marines to dig them out. So they did, with tanks, flamethrowers and bazookas. Unfortunately, the tanks became bogged down in the sodden earth, the flamethrowers igniters would spark, and the bazookas’ rockets would simply stick in the mud rather than explode. When they tried to bring up artillery the trucks would get bogged down and the guns themselves would sink straight into the earth. The marines would have to do their work by hand.

Given the appalling conditions the General Rupertus, commander of the 1st Marine Division, decided to wait until he had more men available. When on the 29th the 5th Marines had finally gotten ashore with equipment and supplies he resumed the offensive. Miraculously, that morning the sun broke through the clouds and the marines prepared to take the airfield. As they advanced they met no resistance. Colonel Sumiya, commander of the Japanese 53rd Infantry had withdrawn in the meantime. Though the battle was far from over the marines had taken the objective and so settled into improving it and their defensive positions. On December 30th Rupertus signaled to General Krueger that the Airfield was taken. The next fight would come when Rupertus would send his assistant commanding general, Lemuel Shepherd to take Borgen Bay, ten miles down the coast from Cape Gloucester to root out the japanese garrison there.

On January 9th, 1944 the 3rd battalion fifth marines began their advance on the town by assaulting the first of two ridges that lay between them and Borgen Bay. The frontal assault cost the marines dearly. The Japanese had constructed a sophisticated network of bunkers and tunnels with interlocking sectors of fire across the ridgelines. Through sheer tenacity and liberal use of mortars the marines were able to drive the Japanese off the ridgeline, mowing them down as they ran for the beaches. They made quick work of Borgen Bay itself and the whole of Cape Gloucester was firmly in American hands by mid January.

Allied forces would hold the western end of New Britain, content with their airfield and the state of Rabaul for now. Patrols would penetrate the jungle as far as 130 miles east, or roughly halfway across the island. The Japanese commander, General Matsuda would flee back to Rabaul via small boat but many of his men were left to find their way back to friendly lines via jungle trails. Nearly all of them starved to death or succumbed to the environment. When Marines patrols would find them wandering the jungle they looked like zombies, their bodies were half rotten and their feet so decomposed they could no longer walk on them. Upon being discovered most would blow themselves up with grenades but the Soldiers and Marines would make prisoners of those too weak to pull the pin. The battle for New Britain cost the Allies just over 300 men killed and 1,000 wounded. 5000 Japanese Soldiers died in the fighting and only 500 were captured.

Operation Cartwheel, the codename given to the two pronged advance up the Solomon Islands and the North Coast of eastern New Guinea to isolate Rabaul, was obviously not an end of itself. The point was to set the conditions for the continued allied drives. MacArthur's ultimate goal was to liberate the Philippines and Nimitz’ was to push through the central pacific toward Japan itself. The Solomon islands proved to be a barrier to both of these operations with the fortress at Rabaul being its crown jewel. The Solomons also proved a suitable jumping off point for both axes of advance. As soon as was feasible Nimitz broke off and began his long slog with the invasion of Tarawa. MacArthur, in conjunction with Halsey, would continue the drive to isolate the Japanese fortress at Rabaul. After the Capture of Cape Gloucester the next step was to close the vice and capture the admiralty Islands, about 250 miles north of Cape Gloucester across the Bismarck Sea, and Kavieng on New Ireland, 150 miles north of Rabaul itself.

In January and February of 1944 the Fifth Air Force set its sights on the admiralty islands and the island of Los Negros specifally. Heavy bombers repeatedly flew over the island, dropping tons of ordinance, but found very little resistance. By mid February they reported no anti-aircraft fire and very little on the ground. Colonel Yoshio Enezaki, the garrison commander, was indeed in dire straits. All of his aircraft operable aircraft were evacuated from the island on February 21st so all he had left were wasted hulks. He ordered his 400 troops, few of whom were actually trained infantrymen, to hid during bombing raids and not to fire their ant-ar batteries.

General Kenney, commander of the 5th Air Force, brought news of the seemingly abandoned airfield at Los Negros to MacArthur’s attention in Brisbane. Los Negros was already scheduled for invasion in late March but MacArthur decided to seize on the opportunity presented to him. The Joint Chiefs and allied leaders had already decided that the drive to the Philippines was taking too long and he figured he could make up for some lost time. So on February 24th he gave the order that the invasion should occur on February 29th, calling it a “reconnaissance in force.” By this point Southwest Pacific forces had over a year and half of experience conducting amphibious operations but five days' notice would be a challenge even for these seasoned planners.

Bumping up the timeline on Los Negros posed a not insignificant risk. For one, a botched invasion would make his forces vulnerable to japanese harassment or counter attacks. He was confident that a swift landing followed up by regular resupply and reinforcement could overcome the ramshackle force present in the Admiralties and that his forces could defeat characteristically piecemeal Japanese counterattacks. Knowing the risks involved he chose to accompany the invasion force himself however. His subordinates and staff were aghast at his decision. There was no need, they argued, for him to be so close to enemy forces and risk his person. He rebuffed their concerns for two reasons I suspect. One, he wanted to make the call himself if the invasion had to be called off and didn’t feel comfortable delegating that decision. Second, he wanted to shake off the stink of Corregidor and any suspicion that he was a coward for abandoning his men in the Philippines two years earlier.

MacARthur boarded the heavy cruiser USS Phoenix at Milne Bay and was off the coast of Los Negros the morning of February 29th as the men of the 1st Cavalry Division went ashore. Despite the tranquil appearance of the island from B-24’s over the previous two months the island was in fact not wholly abandoned. As the landing craft cruised to the beaches, Japanese 20mm cannons raked over the wave tops, threatening the success of the landing. In response the Phoenix, in conjunction with the other escort vessels, opened up with her eight inch guns. She made quick work of the defensive batteries and impressed MacArthur, who had never witnessed such effective shore bombardment before.

With the defenders silent after a good spanking from some well placed naval batteries the rest of the landing went smoothly. Five hours after the first troops hit the beaches at 8 AM Momote Airfield, the primary objective, was in allied hands. AFter the initial resistance there had been little more, a total of 10 casualties were sustained by the Army, four killed and six wounded. The cavalry troopers only found six dead japanese. What they did find in mass quantities were abandoned supplies. There had to be somebody on the island that all of these provisions were for. And there was.

Colonel Ezaki had concentrated his forces on the northern end of the island, believing that was the most likely invasion point. He had assumed this because the location where the 1st Cavalry Division came ashore was not exactly amenable to amphibious operations. Only a narrow channel led to the landing beaches from the open ocean the area is surrounded by mangrove swamps.Had there been stiff resistance by a prepared force the landing craft may well have gotten bottled up and destroyed in the lagoon. Los Negros is only about 8 miles long but the thick vegetation made responding in force to the landings impossible so Colonel Ezaki had effectively isolated himself on the other side of the island from where the invasion occurred. Additionally, Ezaki only had one infantry battalion with him, the majority of his men were members of the transportation regiment that he commanded, elements of a mixed regiment, or the small naval detachment on the island.

With landing area and the airfield secured MacArthur decided to go ashore himself. This was surely the primary reason he had come along, to be seen, and more importantly photographed, going ashore. He had all of the usual stage props, corncob pipe and squashed cap in lieu of helmet in weapon. As he nonchalantly strolled ashore toward the forward line of troops to “see what’s happening” a nervous officer yanked at his sleeve and told him “Sir, we just killed a sniper over there a few minutes ago,” to which he replied “Good, that's the best thing to do with them.”

Several photos were taken of him during the operation. He can be seen on the bridge of the phoenix surveying the ship's bombardment of the shore, making appropriate stern faces. He also made sure to have a photo op of him decorating a Soldier with an award in the immediate aftermath of the invasion when he awarded the distinguished service cross to one Second Lieutenant Marvin Henshaw. The message was clear, MacArthur is back. Before leaving Brisbane he is said to have exclaimed to General Kenney after hearing of the weakened Japanese garrison “that'll put the cork back in the bottle!” I can’t help but wonder if he meant to put the cork in the bottle of the Japanese in the southwest Pacific, or put a cork in the mouths of those who would besmirch his name by calling him Dugout Doug. I tend to lean towards the latter.

Having secured the airfield the men formed a perimeter and prepared for the characteristic nighttime counterattacks that the Japanese were sure to conduct. And of course they did but to little effect. On March 2nd additional troops arrived and 1st Cavalry began to clear out the remainder of the island and by March 15th the entirety of the Division was on the ground with the all of Los Negros in Allied hands and sorties already being flown from Momote Airfield. The first day did not reflect the remainder of the battle however. The Japanese fought with their usual tenacity inflicting nearly 1,500 casualties including 300 killed and over 1,000 wounded. 3,000 Japanese Soldiers and Sailors died defending the island, only 75 were captured.

With the Admiralties secured the 40,000 Japanese holed up in the fortress at Rabaul were essentially cut off for the rest of the war. Unlike the landings on New Britain the capture of the Admiralty Islands were an absolute necessity and materially contributed to Allied victory in the Pacific. The Airbases in the islands allowed the Allies to project power all the way to Hollandia, now Jayapura Indonesia. The Admiralties proved to be not only excellent air bases but also a vital naval base. With Los Negros there was no need to actually take Rabaul by force and it could simply be bypassed. By moving the invasion date up a month the victory on Los Negros also helped to shift the initiative even more in the allies favor and hastened the New Guinea and Central Pacific Campaigns by relieving pressure on Nimitz to capture Truk.

For the Japanese the loss of the Admiralty island meant the collapse of their south eastern defensive perimeter. A major staging area and fortress was cut off and new defensive lines would have to be fortified in western New Guinea. The bold move to capture the Admiralties also indicated to the Japanese High Command that the allies were willing to make bold maneuvers without warning. How were they supposed to defend against an enemy that could make multiple large landings right under the air umbrella of one of their largest bases? And what were they supposed to do about the Army headquarters that now lay beyond their forward defensive positions? Of course the audacity and aggressiveness of American operations would hardly give them time to answer these questions and instead would spend most of the rest of the war on the back foot, reacting to Allied operations rather than driving the operational tempo themselves.

At the end of 1943 and certainly by early 1944 the Japanese were staring down the barrel of a true strategic dilemma, one that they had set themselves up for the moment they launched the attack on Pearl Harbor. Sure, they had run rampant across the Pacific for the first 6 months, almost exactly, but after the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway they lost the strategic initiative. Once the marines landed on Guadalcanal and secured the Airfield the turning point in the war had probably already been reached. The Solomons were very much the gateway to the rest of the Pacific and Guadalcanal was the gateway to the Solomons. After securing the power projection point that was Henderson field the allies gained a significant advantage and Operation Cartwheel could proceed apace. For eighteen months the Amercans and Australians would drive their way up the chain and by March 1944 it was a settled matter. Nimitz was already pushing his way into the central Pacific and MacArthur was only two or three hops away from returning to the Philippines. MEanwhile, the Japanese were still tied up in a massive land war in China, one that they may well have viewed as the primary conflict since its where the majority of their troops were tied up and it was much closer to home. Sure, they had suffered some setbacks in the far reaches of the Pacific but the Americans were still thousands of miles away from sacred Nippon. The war in China was literally much closer to home. Unfortunately for the Japanese it would be the encroaching Americans, taking one island at a time, and slowly but inexorably creeping closer, that would prove to bring their doom.