Episode 48: the China Update, Part 1

So in this episode we are talking about China. We are nearly 50 episodes in and I think I’ve spent a total of maybe ten minutes talking about one of the largest theaters in the war in terms of both land area and number of people involved. The only real mention China has gotten was back in episodes 15 and 16 when I talked about Japan’s rise and early war. The war in China was absolutely massive , it lasted 8 years and 14 million Chinese died during the conflict with Japan. Not only that but the Chinese played a material role not only in defeating Japan but ensuring the survival of the Soviet Union to defeat Nazi Germany.

For many in the west, the role China played in the war is often downplayed or treated like an afterthought when in reality they were regarded as a major ally in the war and Chiang Kai Shek was treated as something like an equal between Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin. For some reason, in the post war reckoning of the war China’s story faded, likely due to Cold War politics and the eventual triumph of Mao Zedong and the communists who themselves wanted to downplay nationalist achievements. At the time however China was given greater credit for its part I think. Going back to the late 1930s China’s fight against Japan was considered a part of the global struggle against authoritarianism, spiritually linked to the Spanish civil war and the fight against the falangists in Spain. Even on this show I’ve given China short shrift and my lack of knowledge concerning China was a known blindspot to me when I started the show. Well, I’ve worked on rectifying that in the past year or two and here we are; the big China update. In the same way that we covered the European and Pacific theaters I want to start incorporating China in the narrative. This will also include the China-India-Burma, or CIB, theater but I find when people talk about China India Burma they tend to just focus on the Burma road and commonwealth forces in Burma. I intend for this to be much broader than that.

What that means today is that I need to set the scene and get us caught up. I spent two episodes describing Japan’s rise to imperial power and early war in China from their perspective. Now I want to do something similar for China, because frankly China deserves it. Big shout out here to Rana Mitter and his book “Forgotten Ally” for completely overhauling my understanding of the Chinese theater of war. Lets begin correcting that mistake right now with episode 48: the China Update Part 1.

By the early 20th Century China was a sad reflection of what it had once been. For millennia the Emperors of China had ruled the Han heartland and the coast of China creating a veritable hemispheric hegemony. The Emperors ruled by the mandate of heaven pulling into their orbit the surrounding peoples in Japan, Korea, the interior steppe and the jungles of southwest Asia. Several times imperial dynasties had fallen but were always replaced, most recently the Ming Dynasty had been usurped by the Qing in 1636, who were in fact not ethnic Han but Manchus from modern day North East china. The Manchus quickly adopted Chinese practices and modes. Much as the title of Caesar persisted in Europe long after the fall of the Roman Empire so to was the cultural weight of the Middle Kingdom that its conquerors adopted its language, practices, titles, and offices.

The Qing state run by its Manchu officials blossomed in the early modern period. A rational system of competitive examinations provided a route for intelligent but low born men to enter into officialdom and fostered a merit based system. The arrival of foreign traders in the mid 17th century spurred a period of massive economic growth in China much as it did in the rest of the world. In this first period of globalization massive silver galleons plied their trade across the Pacific bring ing not only wealth but new crops. New world foodstuffs, especially maize, allowed Chinese peasants to cultivate new lands. In a land where rice dominated in the south and cereal grains dominated in the north, corn made the dryer, more rugged inland arable.

In the century from 1700 to 1800 the population of China exploded from 150 million to 300 million, that is nearly the population of the United States today! And the goods didn’t just flow one way, chinese ceramics, simply called china, became luxury items demanded at every court in europe. If you are interested in this period, I can’t recommend Charles Mann’s book 1493, his sequel to 1491 enough. I’ve read both books twice and they provide a fascinating look at pre-columbian Americas in 1491 and then in 1493 how the world changed after the discovery of the New World. China was a supremely self-confident civilization, believing itself, like nearly every civilization, to be the greatest in the world and the center of the universe. Unlike the Japanese who turned inward however, China remained open, though still aloof and somewhat uninterested in the widerworld.

Over time the Chinese state would atrophy however. The exams became less a test of critical skills but more a set of antique trivia one had to memorize to enter into the halls of power. The Manchu government, while having adopted many chinese practices, retained many traditional manchu forms at court, remained a small insular bureaucracy that could not efficiently govern the now massively expanded economy and population. This, combined with extreme inflation from the amount of Spanish silver pouring into the country weakened the state's monetary faculties. Just as in Europe, where New World wealth caused massive inflation and instability, so too did it in China. The arrival of westerners en masse in the 19th century and the commodification of opium would prove catastrophic for an already weakened Chinese state.

The 19th century is often referred to as the century of humiliation in China, and for good reason. Between roughly 1800 and 1900 China was repeatedly subjugated, pilfered, and exploited by western powers reducing it from a mighty hegemonic major power to a broken husk of a state. It was not simply outside forces that caused China’s fall from power however, internal divisions exacerbated by the aforementioned problems with Manchu government would bring the country down from within. Two massive revolts rocked the country during this century, one being perhaps the largest civil war ever.

Its hard to say what was the first mover in beginning the 19th century fall but Opium is as good a place to start as any. For centuries opium had been a luxury enjoyed by the elites and wealthy but after the arrival of the British the opium trade grew immensely. British traders who came seeking tea to export back to the west found that if opium could be commoditized and sold in bulk at cheap prices there was much profit to be made. So the tea traders wound up doing just that, selling opium in bulk to the masses. The mandarins and manchus recognised opium for the public nuisance that it was and in 1839 raided the british owned factories in the port of Guangzhou also known as Canton.

When word got back to London that the Chinese had treated British subjects so harshly and violently Lord Palmnerston, the foreign secretary, was enraged and authorized a punitive expedition to teach the Chinese a lesson. Thus the first Opium War started. The gunboats of the Royal navy made quick work of the Chinese defenses in Guangzhou then followed up with campaigns up Pearl and Yangtze rivers. What resulted was the first of what came to be known as the unequal treaties with the Treaty of Nanking. The treaty made the Chinese to cede Hong Kong to the british forced them to open their ports to western traders. Over the next several decades similar events would force the Qing government to surrender yet more territory and rights. Cities like Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Macao all ended up under foreign control whether that be directly under a foreign ruler or by a city concession composed of western expats.

Perhaps the greatest humiliation however was the practice of extraterritoriality. Under extraterritorial law foreigners were not subject to Chinese laws no matter where they were in the country. Any breach of the law by a foreigner under extraterritorial protection would not face justice in a Chinese court but rather in what were called mixed courts which were run by westerners with western interests in mind. This blatant disregard for Chinese sovereignty was a great affront to their dignity and a national embarrassment.

Shanghai was one such “concession” city. Before 1842 it was a small trading city on the shores of the Huangpu River, near the mouth of the Yangtze, but after being opened up to foreign traders in the treaty of Nanking it became a major trade hub. It was governed by three different bodies. Within the French concession, essentially a french colony within the city, a council of frenchmen elected by french colonists rule. There was another concession however, the international concession which was not really a colony of any particular country but instead a sort of independent city government elected by foreigners, mostly British but there were also many Americans and Japanese. Elsewhere in the city the Manchu government had nominal control but in the confusion organized crime thrived. Prostitution gambling and racketeering ran wile but so too did commerce. Shanghai became an entrepot where rising Chinese intellectuals could go to get a taste of the west and mingle with people of all backgrounds.

Along with traders seeking fortunes there also came missionaries, seeking to convert China to christianity. The mostly protestant missionaries did have some success, to the chagrin of the imperial government. One such convert was a man by the name of Hong Xiuquan. A man of humble origins from Guangdong province, Hong Xiuquan suffered a mental breakdown after repeatedly failing the imperial examinations in the 1850s and created a sect of militant pseudo-christianity, bent on creating God’s Kingdom in China. I say psuedo-christianity because one of the founding tenants of the Taipings was that Hong was the younger brother of Jesus Christ and that Hong would regularly commune with his older brother and father in heaven. Generally called the Taipings, the men who followed Hong sought to establish the Taiping Tianguo, or Kingdom of Heavenly Peace. What followed was the largest Civil War in all of history and likely the second most deadly war of all time, following the Second World War.

The Taiping Rebellion began in 1850 with a revolt in Kwangsi and lasted 14 long years during which as many as 30 million people died, roughly ten percent of China’s population. China in 1850 was ripe for rebellion and the Taipings provided a standard around which the pent up rage of the population could muster. The Taiping Armies fought effectively, their organization, motivation, and discipline far outstripping that of the imperial banners. By 1853 the rebellion had spread far and wide, controlling a third of the country including Nanking while threatening Beijing itself. For all of their military success the Taipings were terrible administrators. Their zeal for their prophet and commitment to their religion's strict morality made their rule oppressive and arbitrary, even compared to the oppressive and arbitrary manchus. They also failed to get buy in from the middle or upper classes or much foreign support. After a few years infighting began to plague the Taiping generalship, especially once Hong himself began to withdraw into himself, spending his time in mystical meditative seclusion, along with his women. The Tapings also failed to ever secure a coastal port, denying them access to the outside world.

By the 1860s the Taiping was in rapid decline and imperial armies were conquering Taiping forts one by one with the help of western trained armies. In April 1864 Hong died from eating poisonous weeds and in June Nanking fell. 100,000 people are reported to have died in the battle and its aftermath Hong Chief Lieutenants, or Wangs, were executed and the greatest civil war in all of history was over. China was devastated, millions of people were dead, dozens of towns and cities burned to the ground, and whole provinces laid waste. The Taiping were defeated but the Qing government had to make compromises to do it. One was the creation of “New” Armies. These new armies were not controlled by the central government in Beijing but rather by local officials who were allowed to raise their own armies to defeat the Taipings. This decentralizing of military gave rise to powerful warlords who would not simply relinquish their new found power that the Taipings were dead.

This weakened and fractured state would make China even more vulnerable to abuse from the outside world. The now even weaker and more insular government in Beijing had less influence on the state of the homeland than ever before. Lawlessness and brigands became more common, foreigners could run roughshod over any chinese and abuse by foreigners became commonplace. The sino-japanese war of 1894 served to further humiliate and and weaken china, further demonstrating the ineptitude of the regime. While China was crumbling Japan was modernization and strengthening, as we discussed back in episode 15. By the 1890s Japan was nurturing a small empire and seeking further lands, resources, and peoples to exploit. Now, I don’t want to get into the intricacies of Sino-Japanese-Korean relations in the late the 19th century because its complex and I’m not nearly qualified to speak on it but suffice it to say that for centuries Korea had been within the Chinese sphere of influence and something of a vassal or satellite state. As Japan’s power grew she wished to seize the korean peninsula and add it to her own growing domain.

The First Sino Japanese war resulted in a crushing Chinese defeat. Japanese troops trounced the Chinese Soldiers demonstrating what few military reforms the Qing government had undertaken were ineffective at best. At the treaty of Shimonoseki the Chinese were forced to turn Korea over to the Japanese, who eventually annexed it in 1910, as well as Taiwan. Japan had now, without a doubt, secured its position as the geopolitical center of mass in the east.

Five years following the humiliation of the treaty of Shimonoseki tensions built up and resentment toward foreigners festered until the eruption of the Boxer rebellion in 1900. The rebellion was a peasant uprising, the rebels' affinity for martial arts, often called Chinese boxing at the time, lending to its name. And the name really wasn’t far off, the secret society that initiated the rebellion called itself the yi Ho Quan, or society of harmonious fists.

Antipathy to westerners, crushing poverty, and a vicious drought came together that year to push the peasants over the edge. The rebels exacted their vengeance on any westerner they found and on Chinese christians. As the rebels picked up momentum they laid siege to the foreign legations in Beijing and Tientsin. Unwilling to wait for the ineffective Qing government to put down the rebellion the great powers formed the eight nation alliance to quell the boxers. Consisting of the United States, Austria-Hungary, the British Empire, France, Germany, Italy, and Russia, each nation sent troops to put down the rebels, the total strength of which reached 20,000. The United States had large formations nearby in the Philippines who had recent experience in crushing rebellions in fighting the Philippine insurrection. The Boxers were put down and the entire province around Beijing was occupied by the foreign armies and Manchuria was occupied by Russia during which time the armies looted and ravaged the landscape. The resulting treaty forced massive indemnities on China and resulted in the permanent loss of Manchuria. Once again China was humiliated and occupied, her sovereignty trampled.

After successive defeats and humiliations even the backward looking and insular imperial court in Beijing had to acknowledge that something needed to change. In 1902 the Qing began a series of reforms meant to transform the country into a constitutional Monarchy on the model of Japan. These reforms included the creation of representative bodies which at first were organized at the local level but were to eventually include a national assembly of some sort. These Xinzheng, or New Government, reforms were too little too late however.

There were simply too many vested interests that did not consider the survival of the regime to be in their own best interest. The regional military powers were reluctant to surrender their broad powers to a strong central government or newly appointed bureaucrats or a professional officer corps. The middle class were ostracized when, in 1905, the government exams were reformed. The old parochial test was updated to better reflect what was needed in a modern bureaucracy by testing for things like foreign language skills, science, and math instead of ancient confucian philosophy. The aristocrats and bourgeois had spent their lives studying for the old test however, spending small fortunes preparing and felt disenfranchised when their life's work was seemingly made meaningless overnight.

By the early 20th century the population demanded more than modest and gradual reforms, revolution was on the people’s minds. It was in this environment that Sun Yat Sen, the grandfather of Chinese liberalism and godfather of the Kuomintang entered the historical stage. A doctor and a christian from Guangzhou Sun Yat Sen spent the last decades of the 19th century fomenting revolution, moving about secret societies and revolutionary circles, even leading his own secret fraternal organization. For his work the Qing put a bounty on him so he fled to Japan, now the center of learning and enlightenment in the east.

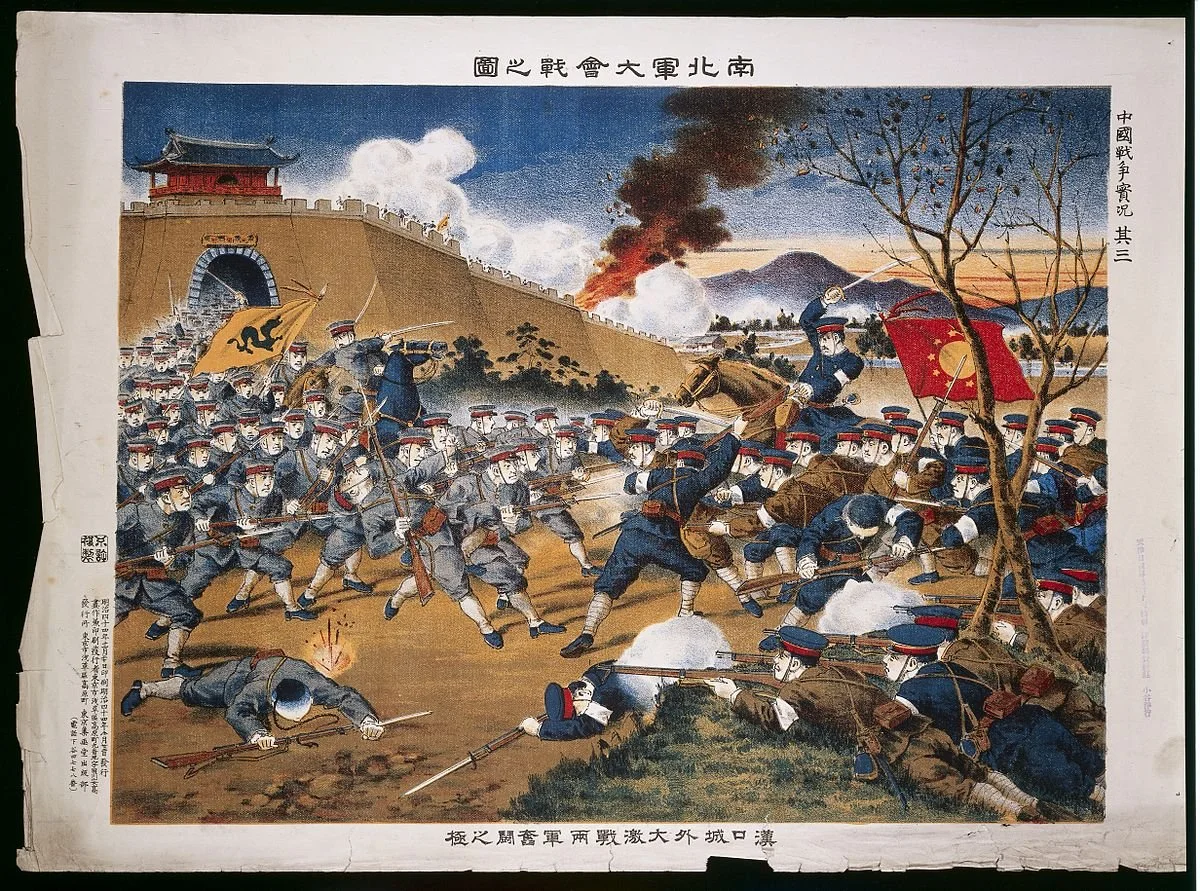

Revolutionary fervor boiled over in the fall of 1911. The Wuhan garrison had become infiltrated by revolutionaries who had been caught in a bomb making plot. When the authorities came to arrest the Soldiers they staged a counter march to the military headquarters and presented an ultimatum to their commander, join the revolution or die. Their commander, knowing which way the wind was blowing, committed his whole garrison to the revolution and declared Wuhan independent of the Qing regime. As news of the revolution in Wuhan spread, so did the revolution itself. Other cities and revolutionary cliques copied Wuhan’s example and declared their own independence.

The newly created provincial assemblies joined in the revolutionary spirit as well and declared themselves part of a new Chinese Republic and appointed Sun Yat Sen as its first President. The old regime proved fragile and all it took was a gentle shove to topple it. That is not to say there was no fighting, there were some skirmishes between revolutionaries and imperial troops but the whole thing was a relatively bloodless affair when compared to something like the Taiping Rebellion. In early 1912 the writing was on the wall so Yuan Shikai, commander of the largest imperial army in China, proposed an end to the fighting. He offered the abdication of the 6 year old Puyi Emperor if the revolutionaries would allow the boy and his household to live out their days with a pension and estate. The revolutionaries agreed and thus, on February 12th, the last emperor of China abdicated; China was a Republic.

China’s experiment with liberal government would not last long. Despite selecting Sun Yat Sen as the first President, real power still lay in the old hands and militarists. Yuan Shikai in particular remained an influential figure and in less than a year he had deposed Sun. This did not stop Sun completely however, he still ran in the parliamentary elections held late in 1912 when his Nationalist Guomindang/Kuomintang Party won the majority of seats. Things took yet another turn for the worse in Mach 1913 when the Guomindang candidate for Prime Minister, Song Jiaoren, was assassinated, likely by Yuan. In the turmoil that followed Yuan dissolved parliament and Sun fled the country for japan.

Yuan remained in power until he died in 1916 but he negotiated away many of China's rights and status to Japan at that time. With the west distracted by the first world war Japan took advantage of the power vacuum to exact tribute from China including forcing China to accept Japanese military attaches, extortionary trading rights, and territorial concessions. After his death, the country descended into warlord-ism. Generally the government in beijing was considered the recognized, legitimate power in the country but this was mostly a polite fiction.

Following the end of the war in Europe the German held territories needed to be divided up. China had hoped to have the German held cities returned to the Beijing government. China had cooperated with the Entente, even sending 100,000 laborers to Europe to assist with the war effort. When the Versailles treaty granted Germany’s former colonial possessions in China to Japan, the Chinese were once again furious and humiliated. News of the west’s betrayal led to massive student protests in Beijing. On May 4th, 1919 three thousand students marched to the foreign legation and to the house of the ministers they deemed responsible for the humiliating treaty. They demanded a rational government, modern, liberal government and their march grew into what became known as the May the 4th movement.

At the same time that something like western liberalism was finding a home in the Guomindang, the Chinese communist party was coalescing. The first chinese communist party congress was held in 1921 and the triumph of the 1917 Revolution in Russia gave chinese communists hope that, perhaps, they too could transform their country. The CCP ws a fledgling party however and hardly had a base of support in the early 1920s. After the death of Yuan the Guomindang found a base of support in Guangzhou where the warlord Chen Jiongming provided protection for the nationalists, allowing the party to organize.

For years Sun Yat Sen had been seeking foreign aid to raise the profile of the Guomindang and to help unify China under the Nationalists rule. Generally he met with little success, the west was either uninterested or pre-occupied despite Sun spending years campaigning and fundraising in Europe and the United States. His big break came in 1923 when the newly formed Soviet Union agreed to an Alliance with the Guomindang. In a show of commitment Sun dispatched a delegation to the Soviet Union including the up and coming Chiang Kai-Shek.

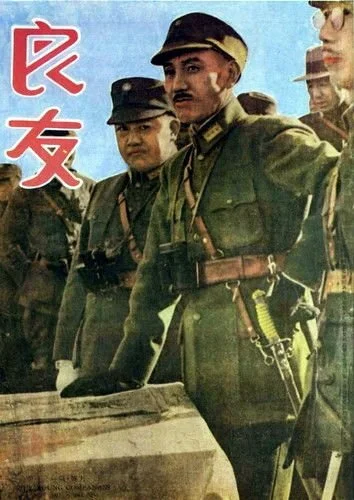

Chiang had been born to a merchant family in Ningbo, a city on the Yangtze delta in 1887. His middle class upbringing had provided him with a traditional, confucian education. He aspired to a military career from his youth, believing that China must be united and cast off the yoke of foreign imperialism. He first attended a military academy in North China before leaving for Japan in 1907 to attend the Tokyo Sinbu Gakko, a military school run by the Japanese Imperial Army for Chinese students. After graduating he spent three years in the Japanese Army until 1911.

Chiang’s time in Japan not only provided him with a military education but a revolutionary one. Many aspiring young Chinese went to Japan to learn modern sciences and thought, including military science. Chiang was ever an enigma to his both friends and colleagues, not to mention enemies. Few knew him well but he was certainly a sharp political player and military thinker but one vice he could never be accused of is indecision.

Japan in the early 20th century was a veritable hotbed of revolution and Chinese revolutionaries and it provided Chiang with the knowledge and connections he needed to be set up for success when he returned to China in 1911. For his role in the Xinhai revolution and his up-and-coming status in the party he was selected for the delegation to the Soviet Union. Chiang’s star was clearly rising and his political fortunes growing but his time in the Soviet Union did nothing to improve his opinion of communism. He found the soviets conceited and autocratic, which seems a reasonable conclusion based on what 1920’s Moscow was like. Lenin's Bolsheviks were consolidating power and instituting draconian measures to do so while constantly lecturing about workers rights. He came away from this experience with a lifelong revulsion to communists.

For the actual Chinese communist party the alliance with the Soviet union was something of a double edged sword. The Soviet Union was not only home to the most successful communist party in the world but also the Communist International, or simply COMINTERN, the world wide governing body for all communist parties meaning the CCP basically had to take orders from them. The COMINTERN more or less ordered the CCP to enter into union with the Nationalists forming the United Front.

While this gave the communists ample room and opportunity for recruitment and expansion it also essentially melded the two parties together. The Nationalists and the communists worked together from 1923 to 1927 during which time influential men in both parties honed their skills. Zhou Enlai, later to be Moa’s Premier, served in the Political Education department under Wang Jingwei, a giant in his own right in the Guomindang. Chiang Kai-Shek would be named commander of the National Revolutionary Army in 1926 and Mao Zedong would become the director of party Propaganda in 1925.

Mao was about as different from Chiang as one could get personally. Where Chiang was quiet, harsh, and distant, Mao was gregarious and out-going. Born in 1893 in Hunan province to a wealthy peasant family, Mao did not get along with his conservative traditional father so left home early to take up political journalism. Like Chiang, he yearned for a free and united China but unlike Chiang he thought a total transformation of society was necessary to pull China out of the past and into the future. When the Xinhai revolution broke out Mao joined a group of armed revolutionaries in his home province and began his revolutionary journey.

In 1925 the whole of China seemed once again primed for mass civil unrest. In May workers in Shanghai protested mass lay-offs in one of the city’s major factories. The police, administered by the british but with Sikh patrolmen, quashed the labor protests but killed 11 protesters in the process. News of the event spread like wildfire resulting in yet more protests and marches across the country. Then in June another massacre occurred in which foreign troops killed 52 people, including school children. The situation may well have been exactly what Sun Yat Sen needed to garner nationwide support and establish the Guomindang as the national government. Except he had died of cancer in March so there was no clear leadership for the party.

In June of that year Wang Jinwei was named head of the political council and essentially head of the party. For the next year the party and country existed in an uncomfortable state of flux. In June of 1926 Chiang was appointed the head of the National Revolutionary Army, the party's military apparatus. He led the army as it conquered and coerced city after city to acquiesce to the Guomindang. Many feared the arrival of Chiang’s army, believing it to be communist aligned since the Guomindang was allied with the Soviet Union and contained communists. The Army’s greatest victory came in 1927 when it captured Shanghai. This not only cemented the Guomindang’s power in the country but also Chaing’s place within it, essentially allowing him to eclipse Wang Jinwie, widely considered Sun Yat Sen’s protege and successor.

The capture of Shanghai also demonstrated just how far off many of the people’s suspicions of the Guomindang’s communist credentials were. The CCP had deep roots in Shanghai and chiang feared their influence as a rival faction within the nationalist government so he had them eliminated. Before even entering the city Chiang had all of the communists identified so that upon his arrival he could have them rounded up and executed. Thousands were rounded up and murdered, many of whom were lieky innocent.

With the nationalists' sudden betrayal of the communists the CCP fell out of alliance with the Guomindang. The communists, including Mao and Zhou Enlai fled Guongzhou for the interior of the country, to go into hiding and begin rebuilding the party away from the nationalist’s centers of power. With the communists now out of the picture and with the backing of the army Chiang had effectively ousted Wang Jinwie. Wang attempted to form a rival government but without the backing of the communists or the army he had no real hope for success. Out of power he receded into the political wilderness.

In 1928 Chiang capitalized on his success and established a nationwide government in Nanking that would be recognized outside china. In reality the country remained divided. The nationalist government controlled the coastal provinces around Nanking but the further from Nanking one traveled the more tenuous that hold became, many areas remaining autonomous or only nominally under the control of the central government. Chiang and the nationalists would undertake a massive program of modernization and industrialization throughout the 1930s however. The railway system was expanded and the total distance of paved roads would double during the decade up to 1937.

The establishment of an actual legitimate government in China as opposed to the personal kleptocratic fiefdom of an opium addicted warlord was quite alarming to the Japanese. Playing strongmen off against each other and leveraging legation coastal cities had proved to be an effective strategy for the Empire of Japan. Having someone like Chiang in power and quickly consolidating more of it threatened their ability to wantonly exploit the mainland. The two governments would soon begin to clash.

The first row came in September 1931 when the Kwantung Army orchestrated the Manchurian incident. They claimed that the local population had grown disenchanted and thrown off the yoke of the warlord government of Zhang Xiulang. In its place the Kwantung Army formed a sort of satellite state of Japan called Manchukuo. There was little enthusiasm in China to resist Japanese encroachments however. Manchuria was not considered part of the territorial core of the country and the mostly Han Chinese population did not wish to spill blood to retain it. So the Nationalist government did little more than lodge protests with the League of Nations.

The loss of Manchuria was nonetheless a massive blow to Chiang’s power and influence. Chiang needed to prove that he was China’s indispensable man. So did the only thing he could to prove it: he resigned. Following his resignation a short period of political chaos ensued. There were protests in the streets demanding Chiang’s return, the military refused to accept the authority of the new head of government, and local governments would not transfer tax revenue to the central government in Nanking. Chiang’s gamble had paid off and he was quickly restored to government, bringing his rival Wang Jingwie in under him.

After returning to power Chiang was again faced with a national crisis in 1932 when street fights broke out in Shanghai between Chinese laborers and Japanese monks. The Japanese naval garrison commander saw this as an opportunity to gain prestige for the navy which was feeling emasculated after the Japanese’ Army’s success in Manchuria yet emboldened by the Chinese lack of response to that conquest. He unleashed his forces on the Chinese population, prompting Chiang to send the Chinese 18th Route Army to fight back. A small war had broken out between the two countries in the city with trench lines and Soldiers lining streets and alley-ways. The fighting only lasted three weeks but it was savage. Thousands of Chinese and Japanese Soldiers died along with roughly 10,00 civilian inhabitants of the city.

Chiang new his country could not fight a general, protracted war with the Japanese so he agreed to terms. They were characteristically embarrassing and humiliating for China essentially removing the Nanking government’s right in Shanghai. Adding insult to injury, the communist party declared that they would never have folded to Japanese demands so easily and would resist them at all costs. This caused Chiang to be even more bitter towards the communists and to see them as yet another dividing factor in the country.

Despite his growing reputation as an appeaser Chiang ws in fact desperately trying to prepare for war with Japan. His primary goal was to at least create a small, professional Army within the larger National Revolutionary Army which was more of a loose association of militias than an actual unified Army. To do this he brought in German advisors, first Hans von Seekt who was followed by Alexander von Falkenhausen. Their job was to drill the Army in german methods and create a professional core capable of taking on the Japanese Army. roughly 80,000 men would go through the german style training regime. A decent number, but only a fraction of the millions of men that would be put under arms in china.

While attempting to arm China and unify the country against what was an inevitable confrontation with Japan, Chiang remained ever challenged by internal disputes and dissent, especially with the communists. The CCP was weak in the early 1930s however. In the wake of Chiang’s 1927 purge they had fled to Jangxi province where they formed a sort of semi-independent government where they could experiment with communist ideas. The communists proved to be at least as dangerous to themselves as the nationalists were. The radical reforms they implemented were deeply unpopular with the population and factional infighting became increasingly problematic. At the same time, after the truce with Japan in Shanghai the nationalists were able to redirect forces to fighting the communists once again. Unpopular, under siege, and constantly engaged in internecine bickering the CCP had to make a bold change. What resulted was the long march.

Since mythologized in the annals of CCP history as a formative moment for the party that forged the party’s leaders into heroes and legends the long march was in all reality a humiliating retreat. In June 1934 the party and all of its loyal adherents packed up and began walking northwest, in search of a new home. 80,000 men women and children marched into the proverbial desert, when the march came to an end nearly 18 months later in Shaanxi province only 7,000 remained. The Long March was formative in two key ways however, Mao emerged as the undisputed leader of the Chinese Communist Party, and the party had reached the nest from which it would build itself up into the CCP that would conquer the whole of the country.

Just before the communists had reached their mountain strongholds in Shaanxi, the political landscape had shifted beneath them once again. With the rising threat of fascism in Europe, the Soviet Union and the COMINTERN had declared a global struggle against fascism. This meant that the CCP was to follow orders and cease fighting against the Guomindang and once again enter into coalition with them. It may seem odd that the Soviet Union would force another communist party into a subservient position with a non communist party but the fact was Stalin was terrified of an even weaker China. If China fell, or collapsed he would no longer have a buffer between his eastern flank and Japan. As long as China remained at least a minimally functional country he could rely on them to be a faithful ally of convenience against the Japanese. He understood the Chiang was all that held China together and did not want the CCP to destroy a solid geopolitical fellow traveler.

Once the CCP had settled they began to enter into talks with the Guomindang to figure out exactly what their arrangement would be. Chiang acted fairly aloof toward the communists, feeling that they had been thoroughly routed and not worth his time but agreed to negotiate regardless. Shortly after they had come to terms, in December 1936, Chiang went to inspect troops in Xi'an. There something completely unpredictable happened: Chiang was abducted.

Zhang Xuiliang, the deposed warlord from Manchuria, had ordered his troops to surround Chiang’s villa and hold him hostage. Zhang was not a communist sympathizer or making a bid for his own power however, he was instead what could probably best be described as a Chinese ultranationalist. He was angry with Chiang for continuing the fight against the communists when the true enemy, the Japanese, was ever growing. Little did he know that Chiang had just concluded an agreement with the CCP to end partisan fighting.

For two weeks Chiang was held in confinement and the whole of China held its breath. Zhang Xiuliang meanwhile became more and more unpopular while pressure mounted to launch a raid to get Chiang back. His wife, Song Meiling, ever his muse and often his mouthpiece cautioned against this however and negotiated his release. Zhang was taken into custody and held under house arrest until 1990.

The detente between the Guomindang came just in time. The United Front would fight as one against the Japanese, at least in name, and their armed forces would fight together. There were still semi-independent warlords through out the country, especially in the border area between Beijing and Manchuria. Though nominally under Nationalist control these areas were really more the personal domains of the local generals who all had “understandings” with the japanese. This inherently unstable situation would lead to a skirmish at a small village called Wanping in July 1937 between the Chinese 29th Army and the Japanese North Garrison Army. history remembers this event as the Marco Polo Bridge incident. Though the two countries were not yet locked into the years-long struggle that would follow, all of the conditions had been met for this border skirmish to transform into a massive war that would last for years and cost millions of lives.