Episode 49: the China update Part 2

In July of 1937 the area surrounding the Luquoqiao, or Marco Polo Bridge as it was known in the west, was essentially countryside at the edge of Beijing, 15 kilometers away. The area was awash in Soldiers however making it a veritable tinder box. Small incursions and flare ups happened from time to time between the Chinese and Japanese forces. On the surface, the incident on December 7th appeared no different. That day Japanese troops accused the Chinese of kidnapping one of their men out on patrol and demanded the right to search the town of Wanping for their missing man.

The local warlord, Song Zheyuan, was under orders to resist any further Japanese incursion but not to spark an international incident. When Song’s troops refused the Japanese’ demands, fighting broke out in the vicinity of the bridge. In the past these sorts of flare ups had been resolved by the Chinese backing down and making some sort of concession. This time Chiang had another outcome in mind.

If left unchecked, the incursion at Wanping could easily spiral out of control and allow the Japanese to occupy even more of north china, including Beijing, a critical railway and transportation node providing access to China’s heartland. Perhaps even more significanttly, the loss of the old imperial capital would represent yet another crushing blow to China’s, and Chiang's, prestige. Chiang had sensed the public mood and knew the population, or civil society at least, was ready to stand up to the Japanese. Thus he ordered the local commanders, who had already begun negotiating for a ceasefire with the Japanese almost out of habit, to resist.

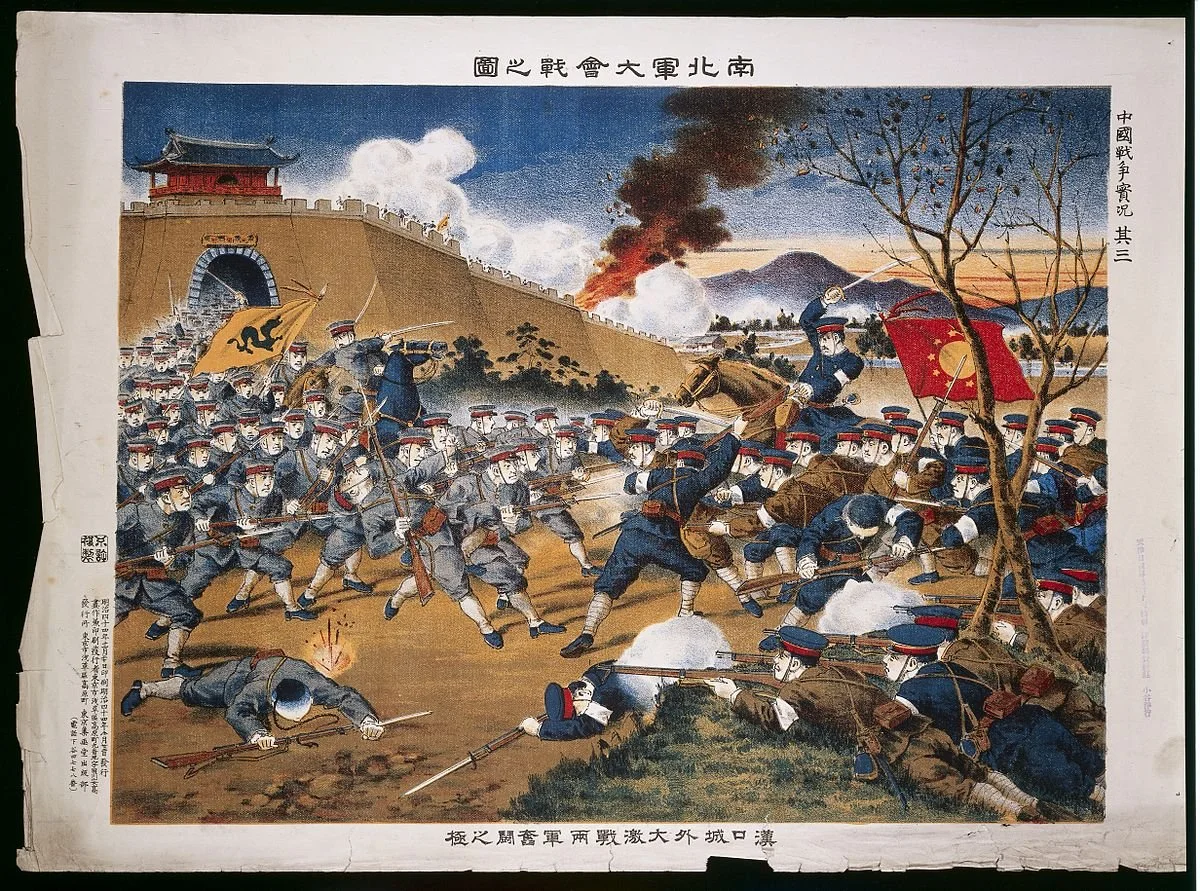

The Japanese government was rather unwilling to follow the Kwantung Army into general war with China but they felt that if they dealt a strong enough blow quickly enough they could dissuade the Nanking government from mobilizing for war. On July 26th, 130,000 Japanese troops launched a massive attack on Northern china. They would not be going up against China’s best soldiers, those trained by German advisers, but rather warlord troops under Yan Xishan and Song Zheyuan and the results reflected that. Though fighting in north china lasted for weeks and dragged into late august Beijing and Tianjin fell within the first week. This is not to say the troops in north china simply folded. The fighting in the area was intense, hundreds of thousands of men were involved and the armies would suffer tens of thousands of casualties.

Chiang had been caught in yet another strategic dilemma in north china. He had to resist the Japanese, there was no question, but he could not risk his best troops on an operation that seemed doomed to fail. He needed to save the crack Soldiers of the Chinese Central Army for operations around the Yangtze valley in order to protect Shanghai and the Capital at Nanking. Chiang needed more men in northern china however and so approached the communists. On August 2nd, Chiang legitimized the Red Army, adding 45,000 men to his army's rolls with only a few strokes of the pen. It was a fateful decision, Chiang had long been loath to allow the communists to maintain an independent army but the necessities of war forced his hand but the final repercussions of that decision would not be felt for another ten years.

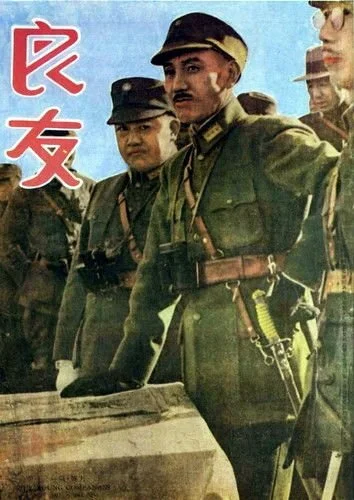

Chiang could not simply will the country to war on his own however, he needed the support of his ministers. On August 7th, he convened a Joint National Defense meeting in Nanking. All of the most important leaders of the Nationalist government were present including Wang Jingwei and relevant ministers and strongmen. During the meeting Chiang gave an impassioned speech that set the tone for the rest of the war.

He argued that the time for appeasement was over, that Japan was seeking to destroy Chinese sovereignty, and that if they could win the war they could revive the country. Chiang was framing the war as a spiritual continuation of the 1911 Xinhai revolution that would forge China into a modern country and world player. Framed in this light, surrender to Japan became not just a question of geo political expediency but rather of national pride, it became a matter of Chinese identity itself. At the close of the meeting Chiang ordered all in favor of war with Japan to stand. Chiang looked to Wang Jingwie, a longtime advocate for peace, he looked to Yan Xishan, his old military rival and northern general, and all the others. Every man among them was standing.

Even as the heads of the Nationalist government were meeting to decide the fate of their country, the north was essentially already lost. It was in the Yangtze valley that the real stand would be made, starting with Shanghai. Chaing would commit his best troops, the 87th and 88th Divisions, to the city’s defense and on August 13th the order went out for the Armies to begin the defense of the city. The Chinese Central Army arrived in Shanghai shortly thereafter and began making preparations for the city’s defense, digging trench lines and fortifying buildings within the city itself.

At the same time the Japanese were strengthening their already substantial position within the city, bringing in 100,000 troops from Manchuria and Taiwan, which was still a Japanese colony. In an attempt to at least marginally disrupt Japanese forces the Chinese air force launched a raid against the Armored Cruiser Izumo docked in the Huangpu River. The raid was a disaster, most of the bombs landed in populated parts of the city killing and wounding hundreds at little cost to the Japanese. The event came to be known as Black Saturday and was supremely embarrassing for Chiang’s government which was struggling to portray itself as competent and capable. The increasing hostilities and outright battle happening in the streets initiated an enormous refugee crisis that would plague the country for most of the war. At least 50,000 people either fled the city or saught refuge in the international settlements.

The increasing Japanese presence and the botched air raid on the Izumo were setbacks but Chiang still had fight in him. He used the growing threat against Shanghai as a means to coerce his rivals, typically unwilling to provide manpower, into sending their own troops. He used the fight in Shanghai as a litmus test, a way for incalcitrant warlords to prove their loyalty not to Chiang but to China. The incorporation of the warlords that had for so long evaded him was now hurried thanks to the imminent threat of Japanese bayonets. By the time Shanghai fell Chiang was able to marshall over 200,000 men to the fight from across China. The impending Japanese threat also prompted the Soviet Union to become more actively involved, first signing a non-aggression treaty with the Nanjing government then beginning military aid shipments including 300 aircraft and 250 million dollars worth of war materiel.

The battle for Shanghai would last a little over three months. By the end of October chinese troops were attempting to withdraw to more defensible lines but the Japanese were not only overpowering them but also outflanking them. The Japanese ferried in 120,000 additional troops and then on November 5th landed troops 150 km south at Hangzhou bay. With Japanese armies threatening his flanks Chiang had to withdraw troops to defend the southern approaches. The writing was on the wall for Shanghai so on November 8th secret orders were dispatched to prepare to abandon the city. Then on November 12th the order was formally given to retreat. Most of the units involved in the fighting were in tatters at this point and the retreat was disorganized at best.

After the fall of Shanghai proper the army tried to establish several defensive lines between the city and Nanking but each was subsequently penetrated by the japanese. The Chinese Army was simply too battered after the fighting in Shanghai and the hasty nature of the defensive preparations made them ineffective. By December the Japanese Army was already threatening Nanking so the Nationalist government had to relocate.

The military command would remove itself to the city of Wuhan, about 350 miles upriver on the Yangtze. The Civil administration would move even farther upriver to Chongqing, 900 miles inland. The nationalist administration undertook a concerted effort to move not only the government itself but also take as many people and as much industry with them as possible. Much like the Soviet Union's vaunted efforts to relocate industry east of the Urals, Chiang's government undertook a similar effort to preserve as much of their warfighting capacity as possible. The government provided for the evacuation of 25,000 essential workers to move west to continue to perform technical functions.

Factories were deconstructed and moved west on barges as well. They would disassemble machines and equipment to load them onto barges which would then be covered with reeds or otherwise camouflage to hide them from Japanese bombers.

For the majority of Chinese fleeing Japanese occupation however the journey was grueling and long. They moved by train, barge, and foot across vast swathes of the country. Journalists traveled with them documenting their travails. Near Japanse lines the refugees were subject to harassment from enemy aircraft but as they moved inland scarce food, lack of shelter, and their own Soldiers became even larger threats. The mass movement of civilians across the country did have the distinct impact of helping to forge a national identity. People from many different provinces had to migrate together and settle in new places they likely would have never seen otherwise, forging bonds that stretched across the country. Tens of millions of people would be displaced, as high as 80 to 100 million, roughly 10 percent of the whole population.

By the end of 1937 much of northeastern China lay in Japanese hands as well as the lower Yangtze up to the outskirts of Nanking. Communist troops, trained and designed for guerilla activities remained behind Japanese lines and continued to harass them but the major fighting was moving farther inland. Though the chinese armies eventually retreated in the face of the Japanese invaders they had fought a tough defense. Much tougher than the Japanese Army had anticipated. 42,000 Japanese Soldiers had been killed or wounded in the battle for Shanghai. The bitter fighting enraged the Japanese Soldiers and they were looking to exact their revenge.

On December 7th 1937, Chinag Kai Shek left Nanking for Wuhan, he had wanted to remain in the capital as long as possible but with the japanese army approaching the city he knew he had to leave. Behind him he left General Tang Shengzhi. Tang was a warlord from Hunan province with whom Chiang had a contentious relationship. Tang had both been a member of the National Revolutionary Army and an opponent of it but Chaing gave him the command as a test of loyalty. Tang accepted the command, knowing it was a hopeless last stand but wishing to prove his patriotism.

Again, elite troops were withdrawn from the city and less well trained men were left behind to absorb the Japanese blows in a futile attempt to save the city. Among those defending Nanking were troops from Guangxi, and Hunan, as well as some cantonese formations which had been decimated in their retreat to the city. There were also two crack divisions, the 36th and the 88th, which had endured so much attrition that the majority of their trained Soldiers had been killed and replaced with green conscripts.

On December 12th, as the Japanese carried out their bombing campaign against the city, they also bombed the USS Panay, docked in the Yangtze. The ship was sunk and three of her crew were killed. The United states, as well as the interested western powers, were outraged. The Japanese claimed it was a mistake and offered reparations for the bombing in order to prevent increased American involvement.

On the same day, General Tang decided to abandon the city after several days of hard fighting in which 70,000 Soldiers had been lost. As the Chinese armies retreated they set the city ablaze in order to deny as much of it as they could to the invaders. The next day, the Japanese Army entered Nanking.

I’ve already discussed the Rape of Nanking so I won’t belabour it again but suffice it to say that the Japanese army took out their frustrations on the population of the city. Their frustration at chinese resistance, which they had been led to believe would be nonexistent, and their pent up frustrations from abuse during their time in the Army, the Japanese Imperial military was not a pleasant institution to be a member of, combined with nationalistic propaganda to set the Army into a six week murder, frenzy. The rape of Nanking was not the first or the last Japanese atrocity however. Only the single largest and most well known, partly because it was so well documented by westerners living in the city.

The fall and subsequent sacking of Nanking was another massive embarrassment of Chiang and the Nationalist government. It was not so much that the city was lost, which was bad enough, but that the Soldiers seemed to defend it so meekly. The men left behind put up only token resistance before torching the city and fleeing. This was not enough to save many of them however, 30,000 of them were rounded up and murdered by the Japanese after the fact, along with 20,000 other military age men who had not been a part of the Army. The cold logic of an existential conflict drove Chinag’s decisions however. He felt that not only the survival of his regime, or even his country was at stake, but Chinese civilization itself. Chiang would be forced to make similar gut wrenching decisions time and time again during the eight year conflict.

Following the fall of Nanking the Japanese government decided it should formalize its relationship with China. Throughout 1937 there was no actual declaration of war, thus far the whole thing had been an extended military incident legally speaking. On January 16, 1938 Prince Konoye of Japan announced not that they were at war but rather that his government would have absolutely no dealings with the Nationalists. Effectively a declaration of war but also effectively a declaration of an unconditional surrender policy. To the nationalist government the legal situation needed no clarification.

Simultaneously Chiang’s military leadership in Wuhan needed to plan their next steps. They decided that they should forma defensive line at Xuzhou, about 150 miles north of Nanking and 150 miles inland from the Yellow sea. Xuzhou was a key rail juncture in central China. The Japanese also understood the importance of controlling the central chinese logistics hub and themselves launched a campaign to take it. The Japanese advanced in two columns along the Jingpu railway, one from the north, the other from the south forming a giant pincer movement to take the juncture. They poured 400,000 troops into the operation to seize Xuzhou. They took Bengbu in early February providing them with a critical jumping off point for the northern leg of the campaign. Subsequent battles at Yixian and Huaiyuan north of Xuzhou Chinese troops faugh valiantly, often to the death but could not stop the Japanese’ advance. To lead the defense Chiang placed another old rival in command to prove his loyalty, Li Zongren.

By March the Chinese defense was failing and the Japanese Army was driving ever closer to taking their objective. Li Zongren and his lieutenants decided to make a stand at the ancient walled city of Taierzhuang which overlooked not only the railway but also the Grand Canal, a major inland waterway. Loss of Taierzhuang would allow the two advancing columns to link up and assault Xuzhou in their combined strength.

The battle began in earnest on March 24th and quickly devolved into a brutal street fight in which Soldiers fought house to house with grenades, bayonets, knives, and fists. The Japanese even employed tear gas at one point to clear the defenders out of a train station. For two weeks the battle raged but on April 7th the Japanese broke off the attack. The Chinese killed roughly 8,000 enemy in the battle and claimed their first real victory of the war.

The battle of Taierzhuang was a tactical victory but proved to be little more than an operational setback for the invaders. Throughout April and May the Japanese pressed westward making slow but solid gains. In June 1938 they were approaching Zhengzhou, a major urban center about 280 miles almost due north of Wuhan. Zhengzhou lies on the banks of the yellow river, its massive dikes holding the water in its channel. With the Japanese marching westward despite all efforts to stop them, Chiang's government had to do something drastic to stop the invasion in its tracks. If Zhengzhou fell, Wuhan’s northern flank would be exposed and would certainly fall shortly thereafter, threatening the very survival of the Nationalist government. At least that was the logic that permeated the leadership in Wuhan.

Fearing for the very survival of the regime, Chiang made the fateful and terrible decision to blow the dikes and flood the river plain, stopping the Japanese in their tracks. The dams and river walls proved well constructed, when the Chinese army attempted to blast the dikes they held strong so thousands of chinese soldiers were ordered to dig the holes by hand without the help of explosives or even machinery. They did it though, on June 8th water began to flow through the walls down into the floodplain, carpeted with rice patties and dotted with peasant villages.

Chiang had been forced to make yet another gut wrenching decision and he chose the only option he thought realistically available to him but it came at terrible cost. A five foot wall of water rushed out to flood 500 square miles of central china. Within hours half a million people were displaced as the floodwaters washed away their villages and fields. The flood would have devastated the provinces of Henan, Anhui, and Jiangsu. The estimated death toll from the decision is believed to be roughly 500,000 with another three to five million people displaced.

Blowing the riverwalls certainly had an immediate operational impact, preventing the advancing Japanese Army from reaching Wuhan, at least temporarily. But it came at such a massive cost that it hardly seems worth it. The Japanese diverted their forces south along the Yangtze, attacking and capturing the city of Jiujang, 100 miles southeast of Wuhan, in July. Here the Japanese committed yet another atrocity, pillaging and sacking the city after taking it.

News of the destruction of the Jiujiang spread wide, mostly thanks to China’s robust and impressive press, which had a stiffening effect on her Soldiers. The remainder of the season's advance up the Yangtze proved much more difficult. But the Japanese army advanced none-the-less. By October the Japanese had advanced to the outskirts of the Wuhan. On October 24th Chiang boarded a plane to leave the city. The very next day Japanese forces entered Wuhan. The massive sacrifice of half a million people and the displacement of million more had only delayed the inevitable by a mere six months. If you do the math that means each death bought the Wuhan roughly 24 seconds. One life for 24 seconds. Following the fall of Wuhan Chiuang was worried the city of changsha, 180 miles further upriver, would fall soon after so ordered the city torched to deny it to the enemy.

By the beginning of 1939 nearly all of Eastern China was occupied and the Chiang's nationalist government had effectively been exiled to the remote mountainous west of the country. The Japanese controlled the coast and the communists held sway in the northwest. China had suffered immensely, not only at the hands of the enemy but also at the behest of its own leaders, working under the cold logic of wartime necessity. Even after suffering disaster after disaster the country had not broken however. There was still fight left in the Chinese, enough to fuel another seven years of war.

After the chaotic and fast moving first 18 months from July 1937 to December 1938 the war stagnated a bit. There were fewer large, set piece battles and much less territory changed hands. Instead the next period of the war was characterized by the three competing sides, the Nationalist, Communist, and collaborationist governments struggling to find their way in the seemingly endless war. Much of the soul searching was concerned with how to navigate the changing social contract that was developing. Historically, the Chinese state had very little in the way of social programs and the Chinese people were simple subjects who served the state. With war raging, a new understanding evolved wherein the people sacrificed much for the state but with the understanding that the state would serve them as well.

Chong-qing, the new nationalist capitol in the deep interior of the country was a microcosm of this changing understanding. The city’s population exploded from just under half a million in 1937 to over a million by the end of the war. Many of these refugees were assisted and resettled by the nationalists refugee assistance programs. The government in Chongqing knew it had to do something especially since they weren’t the only game in town. People could flee to the communists in Yanan or even return to their homes in the Japanese occupied east, which many people did. After the tumult and chaos of the warlord era many people had little confidence in Chinese leaders and thought the Japanese occupation government couldn’t be any worse. And besides, at least they could return to their homes.

As in most countries in the second world war, feeding the enormous needs of wartime industry meant increasing state intervention in the economy. The Nationalist government had lost most of its major sources of revenue, having relied on import duties in the major coastal cities to fill its coffers. It instead had to set up internal trade controls to make up the difference. While harmful to the economy it at least raised some desperately needed cash which the Chongqing government needed to pay for its refugee programs and its army, which was enormous and took in 2 million men a year.

The communists were not having a much easier time but their isolation in the northwest allowed them to experiment with socialist ideas while improving marxist training for its members. The party also exploded in size during the early years of the war, growing from 40,000 members to over 750,000 and growing the communist Army from 90,000 to over 400,000. One of the big problems the communists faced was that they attracted mostly young revolutionary men. Men outnumbered women by as much as 30 to 1 in Yanan and those women who did come were prone to very conservative communist styles to the extent that one communist activist remarked that “Yanan was really not a sexy town.”

In the east, along the lower Yangtze the Japanese were busy setting up a new collaboration government meant not to just govern in Japan’s name but to rival the Nationalist government in Chongqing. To head up this new government they needed a figurehead with at least some credibility, someone with revolutionary chops but who had been spurned by Chiang one too many times. Waiting in the wings of the nationalist government was the perfect candidate, a man whose reputation would become as spoiled as Phillipe Petain’s or Vidkun Quisling. Wang Jingwie had defected.

Before it even got off the ground Wang’s regime was troubled. It took over a whole year, from when he defected in December 1938 to March 1940, to complete the negotiations with Japan and actually raise his flag over Nanking. Despite taking so long the terms were steeply one sided. Wang’s regime would not govern all of occupied China but really only portions around the Yellow and Yangtze rivers. Manchuria, north China, and southern China would all have their own carve out occupations. The Japanese army retained complete autonomy from his government and Japan maintained economic dominance. Because Wang had always lacked military support he had no security following and had to turn to gangsters to protect him the hit squads dispatched from Chongqing, further tarnishing his regime. Even after his regime was set up the Japanese didn’t fully recognise it until November, because they had been in limited negotiations with Chiang Kai-shek.

The only concession Wang got was that he could fly the nationalist flag. Yes, the same flag that Chiang’s government flew. The only difference was his collaboration government's flag would have a yellow stripe at the bottom. Wang wanted his government to be the true continuation of Sun Yat Sen’s revolution so wanted to use the flag associated with the movement. The Japanese were concerned that this would be confusing, but also didn’t want to lend credibility to any Chinese nationalist movements. But they caved on this one point to get Wang on board.

The situation for free China, as the unoccupied areas were sometimes referred to, had grown worse in 1939 and 1940. Poor harvests in both years increased the economic strain on the the already cash strapped government and the loss of external trade routes blocked most imports. The occupation of the coastal cities, including Guangxi province in November 1939, and the closure of land routes through indochina and burma meant it was more difficult than ever to communicate with the outside world or to move people and goods in or out.

The desperate situation raised tensions between the nationalists and communists as well. Though publicly both sides were committed to the United Front, in the confusing and chaotic mess of internal chinese politics Nationalist and Communist troops clashed along the Yangtze, which acted as a sort of north south dividing line between areas of control. With the communist army growing and becoming more effective, it had undertaken a successful offensive against the Japanese in the summer of 1940 culminating in the battle of the hundred regiments, it also grew more assertive. In January of 1941 the troops of the New Fourth Army marched south against Mao’s wishes and confronted nationalist troops.

The ensuing battle was a bloodbath but the communists came out victorious. This invited reprisal from the nationalist troops who wound up killing or capturing 9,000 communist troops in March. Despite the communists having initiated the incident, because the nationalist forces wound up achieving such a devastating victory Chiang’s forces got the bad press. Afterward, Chiang gave up trying to take ground north of the Yangtze from the communists marked a change of fortunes for the better for the CCP.

Despite the numerous large setbacks for the chinese there were some silver linings. 1941 saw the winds of global geo-politics change prompting the United States to become more involved across the globe. The United States began extending loans to the Chongqing government, 25 million dollars in 1938 and another 45 million in military aid in February 1941. In that same year the AMerican Military Mission in China would be established as well as the China branch of the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS. In July that year the Roosevelt administration imposed their oil embargo on Japan for its actions in China.

Feeling the pinch of the US trade sanctions and eyeing valuable European colonies in Asia, Japan made the fateful decision to begin a war with the western powers. The attack on pearl harbor was a devastating blow to the United states but it was a god send to Chiang Kai-shek. Though ultimate victory was still years away there was now an end in sight. Direct involvement of western powers in the war against Japan was a dream Chiang could never have anticipated coming true and now the Japanese had achieved it for him.